Since the earliest days of cinema, filmmakers have adapted pre-existing stories into movies. Recognizability and built-in fanbases help with the box office, and a narrative that’s already been written can help with the development process (even if it’s changed significantly).

Video games are more narrative and more popular than ever,1 so it’s understandable that Hollywood wants to adapt them into movies and TV shows. They have an advantage over novels and plays, given that they are a visual medium with art and style that can be copied.

That’s the thinking, anyway. Turns out, it can be much more complicated than that.

This is the second part of a three-part essay. The first part is available here.

Dueling Mustaches

2023 saw two movies2 released that were based around some of the oldest electronic games: Tetris and Pinball: The Man Who Saved the Game.3

Neither game has any story to speak of, so what’s an IP-obsessed industry to do? Why, make them into a biopic, of course! The former is about the businessman who brought Tetris to America, while the latter is about a journalist who saved pinball from being banned in New York.

So if they’re not adaptations, why am I writing about them? This is the title screen for the game Tetris on the Game Boy—

And this is a scene transition from the movie Tetris on Apple TV+—

That’s not adaptation, but it’s something right? Drew Morton calls it stylistic remediation.

Adaptation vs. Remediation

First of all, yes, that term is terrible because what we’re talking about has nothing to do with remedying anything. It’s not Morton’s fault, though; the term was coined by Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin in Remediation: Understanding New Media, which in turn is an update of Karl Marx’s theory of mediation. So, really, the term should be “re-mediation.” It’s a post-modern rabbit hole you don’t want to go down, trust me.

But despite it’s terrible name, the concept of re-mediation is helpful in understanding what’s happening in video game movies. As Morton explains in his book Panel to the Screen: Style, American Film, and Comic Books During the Blockbuster Era—

Adaptation is the modification of a prior text from one medium into another. Remediation… is the representation of one medium in and by another.

Remediations are not necessarily adaptations. Take, more broadly, the example of the ebook. This medium retains the content, the form of the book…, and the practice of reading… exhibited in its analog predecessor. The ebook’s remediation does not modify a prior text as it transitions from on medium to another. It simply re-presents it.

Take The Importance of Being Earnest. The play was adapted as major studio releases in in 1952 and again in 2002. But, being the philistine that I am, I was only first aware of it because it’s the play Mary Jane stars in, in Spider-Man 2.

The difference should be fairly clear. The first two clips are from a movie of a play; the last is a play in a movie.

Remediation… with Style

Stylistic remediation, then, is when an adaptation uses stylistic elements of the source material, thus retaining recognizable traces of the original medium's aesthetic or formal qualities.

This can be done for good or for ill. The split-screens in Ang Lee’s version of Hulk, for example, completely misinterpret the purpose and nature of panels on a comic book page. Split screens in movies (usually) represent simultaneity; separate comic panels (usually) represent the passage of time. American Splendor, on the other hand, reframes the panel within the shot.

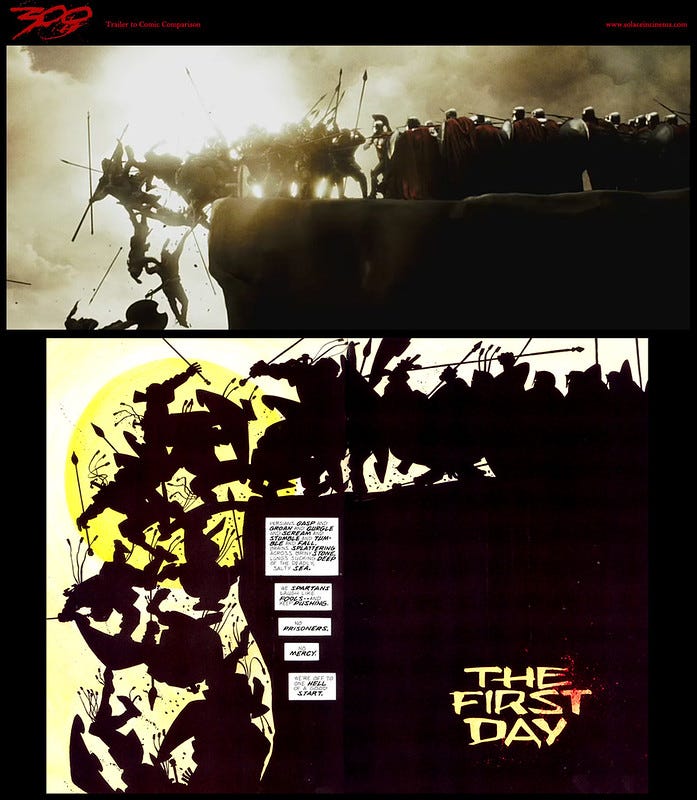

This is more than simply trying to reproduce a shot with a different aspect ratio than the original drawing, as Zack Snyder frequently does in his comic book movies. That’s inherent in his project of faithfully adapting classic works from one visual medium to another.

True stylistic remediation utilizes elements native to the originating medium that aren’t normally present in the new one.

It’s worth asking why filmmakers do this. There are probably a lot of reasons, including Snyder’s desire to “honor” the source material. By it’s very nature, remediated style is something audiences don’t normally get to see; this makes a movie stand out, which is a plus for the studio’s marketing department. But I think the simplest answer is: it’s fun.

The inspiration for my short EXT. LOS ANGELES - DAY was this very concept. No one (well, few people) had put the text of the script on the screen.4

What’s in a Game?

As games have moved from 8 bit pixel art to photorealistic graphics, what is there for movies to re-mediate? Until Dawn, the game, already remediated the slasher film into a game format. What happens when you re-remediate a genre back to its original form?

The answer to that question and more will be found in Part 3.

Many financial comparisons between the two media are disingenuous or misguided, however. They often include everything from the games themselves to the cost of consoles and peripherals on the one side, and compare all of that simply with domestic box office, ignoring ancillary purchases and rentals, not to mention television and streaming. If we’re going to include AAA titles as well as mobile games, we ought to include low-end cinema as well, like YouTube.

Weird, I was just talking about twin movies.

Both are pretty good films, but Pinball had a fraction the budget of Tetris and was a much more clever, more innovative movie. Plus, it was produced in part by my friends at the Motion Picture Institute.

I should probably write a whole post about this one day.