The birth of the reader must be ransomed by the death of the Author.

- Roland Barthes

It’s a pernicious theory that’s been ruining discussions around art for longer than I’ve been alive. If you want a serious and thorough takedown on the concept, I recommend reading Eric Wayne’s article “The Death of the Author” Debunked. But if you don’t have that kind of time, just watch my video essay—

It’s a follow-up to my April Fool’s video, which was a parody of the sorts of dumb fan theories that come about when we put the reader’s perceptions above the author’s intentions.

This free version of the video essay is lightly censored because YouTube’s IP gnomes got riled up about some interview footage, and I had to bleep out some mild swears. Only paid Substackers get the full version!

All Part of the Plan

It’s a common complaint that the Sequel Trilogy didn’t have a plan, but honestly, that was true of the OT and the prequels, too. I’m going to do a video essay some day about the “planning” of each of the Star Wars trilogies, but the ST sucks because the movies suck, as far as I’m concerned.

The lack of planning didn’t hurt the originals. Empire is the best of the entire series, and you can see how it evolved from development to shooting. As I promised in the video essay, here’s the original script for the Star Wars sequel—

According to Deadline, George Lucas wrote a letter1 to Lost executive producers Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse after the finale of their series:

Congratulations on pulling off an amazing show. Don’t tell anyone … but when ‘Star Wars’ first came out, I didn’t know where it was going either. The trick is to pretend you’ve planned the whole thing out in advance. Throw in some father issues and references to other stories — let’s call them homages — and you’ve got a series.

In six seasons, you’ve managed to span both time and space, and I don’t think I’m alone in saying that I never saw what was around the corner. Now that it’s all coming to an end, it’s impressive to see how much was planned out in advance and how neatly you’ve wrapped up everything. You’ve created something really special. I’m sad that the series is ending, but I look forward to seeing what you two are going to do next.

Dying Hard or Hardly Dying?

Die Hard is one of my all-time favorite films, as I’ve mentioned before.

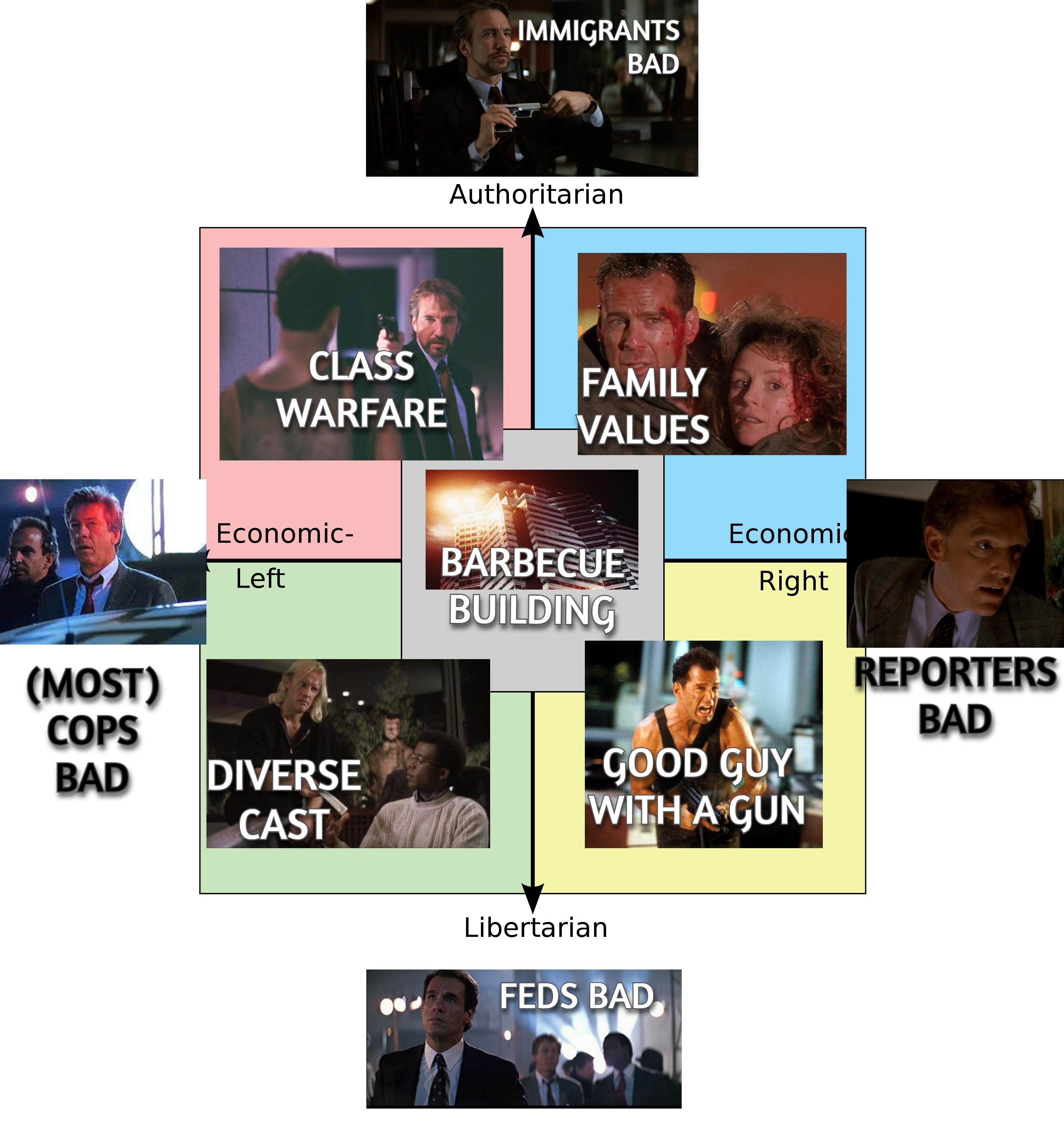

I took the term “strategic ambiguity” from David Bordwell’s essay Superheroes for Sale, but the diverse political interpretations of Die Hard were originally inspired by his piece about cognitive studies in film, Invasion of the Brainiacs II:

Studying how viewers appropriate a film differently is an important enterprise, but so is studying convergence. Arguably, studying convergence has priority, since the splits and variations often emerge against a background of common reactions. A libertarian can interpret Die Hard as a paean to individual initiative, while a neo-Marxist can interpret it as a skirmish in the class war, but both agree that John and Holly love each other, that her coworker is a weasel, and that in the end John McClane’s defeat of Hans Gruber counts as worthwhile. Both viewers may feel a surge of satisfaction when McClane, told by a terrorist he should have shot sooner, blasts the man and adds, “Thanks for the advice.” What enables two ideologically opposed viewers to agree on so much?

Here’s a detailed look at the political compass of Die Hard—

Seriously, What the Heck, Spielberg?

If you weren’t alive in 1984, you may not believe me about the impact of Gremlins. But watch this trailer, and tell me if you think it would prepare a three-year-old for the horrors to come—

Also, we can’t talk about Gremlins without once again sharing the Gremlins 2 pitch meeting sketch from Key & Peele—

Yes, Satan is the Bad Guy

I had always heard that Satan was this cool anti-hero in Paradise Lost.

But when I actually read it, I had the same reaction as Wendigoon—did we read the same book? (I time-stamped his hilarious reaction, but you can also watch the whole video if you’re interested.)

In an earlier draft of my video essay, I used a long quote from CS Lewis’2 Preface to Paradise Lost:

They [the innocence of Adam & Eve, and Satan’s evil] were never, in essence, assailed until rebellion and pride came, in the romantic age, to be admired for their own sake. On this side the adverse criticism of Milton is not so much a literary phenomenon as the shadow cast upon literature by revolutionary politics, antinomian ethics, and the worship of Man by Man.

After Blake, Milton criticism is lost in misunderstanding, and the true line is hardly found again until Mr. Charles Williams’s preface. I do not mean that much interesting and sensitive and erudite work was not done in the intervening period: but the critics and the poet were at cross purposes. They did not see what the poem was about. Hatred or ignorance of its central theme led critics to praise and to blame for fantastic reasons, or to vent upon supposed flaws in the poet’s art or his theology the horror they really felt at the very shapes of discipline and harmony and humility and creaturely dependence.

Filmography

The movies I used as core examples for this essay were: The Shining; the Star Wars trilogy (Star Wars,3 Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi); Fantastic Four (2015, AKA Fant4stic); The Exorcist; Sunshine; The Flintstones, "The Beauty Contest."

Other movies and shows I clipped from included: The Sixth Sense; Gilda; Batman: The Animated Series, "Mad Love"; Contempt; Bluey, "Movies"; Making The Shining (a BBC TV special that appears to be available on only as a special feature on certain editions of the DVD); Kubrick by Kubrick (interview audio); Leap of Faith: William Friedkin on The Exorcist; Captain America: The First Avenger; Deadpool; Shakespeare in Love; Monty Python and the Holy Grail; Out of the Inkwell, “Modeling”; Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery; The Incredibles; Sullivan's Travels; LA Story; Sleep with Me;4 Chasing Amy; It: Chapter Two; Mr. Mercedes, "People in the Rain"; Inception; Die Hard; Mad Max: Fury Road; Annie Hall; The Simpsons, "The Old Man and the Lisa"; Gremlins; Ferris Bueller's Day Off; Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs; Seven.5

This is almost certainly a joke, but I’m sharing it anyways, because I want the urban legend to spread.

If you read my other Substack, The Amateur Theologian, you know how I feel about CS Lewis.

I refuse to call it “A New Hope.”

This doesn’t appear to be available anywhere. As far as I know, the only thing significant about the movie is that Tarantino cameo.

I refuse to call it “Se7en.”

FYI you don't necessarily have to do a video essay on Star Wars. SFDebris has already done a really indepth examination on its creation all the way up to the sale to Disney.

https://sfdebris.com/videos/special/herosjourney.php

https://sfdebris.com/videos/special/shadowsjourney.php

https://sfdebris.com/videos/special/hermitsjourney.php

Lucas at least had an excuse - he had no idea if Star Wars was going to be successful so it makes sense for him to not have a plan beyond a vague outline.

Disney paid FOUR BILLION DOLLARS for the thing. They KNEW they were going to make a trilogy, it was practically demanded of the price tag. They had no excuse for not having a plan other than a cargo-cult style belief that if it worked for Lucas it would work for them. (which just makes it all that much dumber)

"(I time-stamped his hilarious reaction, but you can also watch the whole video if you’re interested.)"

I dig wendigoon and will probably watch the whole video later, but the timestamp seems to have not worked. Which reaction point do you intend?