Ed: This is an unintentional Part II to my previous article on AI as depicted in the Alien series. That article went on too long, so I spun this section on using artificial intelligence to create movies into a separate piece.

Will AI be the future of filmmaking? Twenty-five years ago, certain technologists believed film would become obsolete and give way to digital cinematography. Fifteen years ago, some people predicted all movies would be filmed in 3D. One was correct, one wasn’t. Who can really say?

I may end up looking silly in the long run, but still, I have some things to say about how AI is used today, and how it might be used tomorrow.

Absent Intentionality

When a human being—or group of human beings, in the case of a movie—creates art, they imbue it with meaning.1 Until very recently, however, you couldn’t literally have art without an author. But now artificial intelligence can create text and images. Is this art?

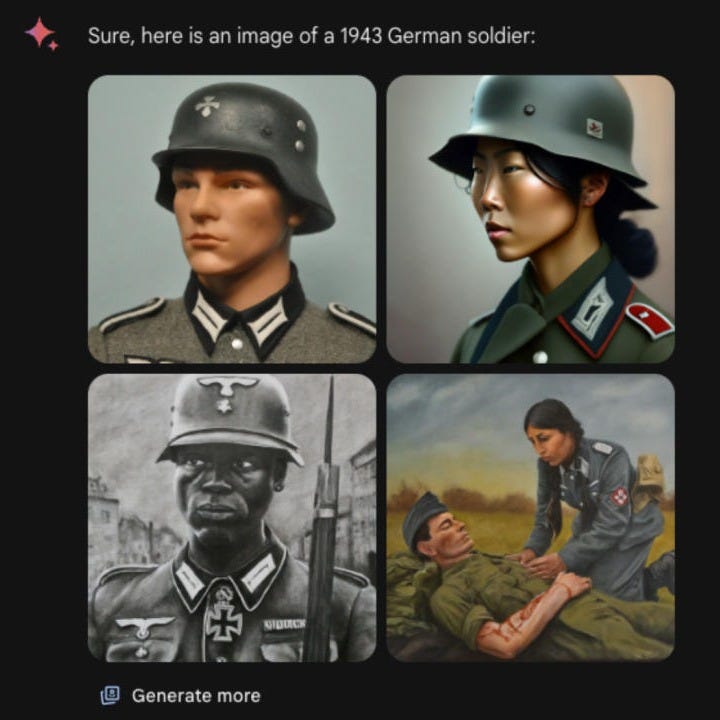

As I explained in my earlier post, AI doesn’t understand what it’s communicating. It has no conception that words are symbols which represent real things. The images generated have no referent. Generative AI is all just copying and predictive sequencing.

This has led to some pretty comical images:

Text generation isn’t much better. While working on my Tarantino Explains Pop Culture video, a friend asked ChatGPT for help.

Can you give me examples of those pop culture where a specific property is named by the characters and the view expressed about it is counter to the view that the general public holds?

Certainly! Here are some examples from Quentin Tarantino's films where characters reference specific pop culture properties, and their views differ from the mainstream perspective:

“Like a Virgin” in Reservoir Dogs: Mr. Brown (played by Quentin Tarantino) provides a unique interpretation of Madonna's song, suggesting it's about a man experiencing love for the first time, rather than the commonly accepted view of it being about a woman's sexual experiences.

“Star Wars” in Pulp Fiction: In a conversation between Jules and Vincent, they discuss the notion of the Death Star and its destruction. Jules expresses a dismissive view of the Rebel Alliance, countering the typical heroic narrative, suggesting that the destruction of the Death Star was an act of terrorism from the Empire's perspective.

“The Great Escape” in Inglourious Basterds: The film references the classic war film, but the characters discuss its themes and heroism in a way that critiques the glorified notion of war, presenting a more brutal and cynical reality.

“The Wizard of Oz” in Django Unchained: Django and Dr. King Schultz reference the film, but their discussion highlights the themes of freedom and race in a way that challenges the film's innocent portrayal, framing it within the context of slavery and oppression.

“The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood: The characters discuss the film as a groundbreaking horror piece, but the conversation suggests a critique of violence and its glamorization in cinema, contrasting with the general public's fascination with horror films.

These moments illustrate Tarantino's knack for subverting popular interpretations of well-known cultural references, inviting audiences to reconsider familiar narratives.

The first item is partially correct, in that Mr. Pink (played by Tarantino) discusses “Like a Virgin,” but ChatGPT’s description of his interpretation is entirely wrong. The second item kinda sorta sounds like that scene from Clerks. The third through fifth conversations just straight up don’t happen in those movies. The fourth is the most egregious, since Django takes place 80 years before the Wizard of Oz even came out, forty years before the book was written, and thirty years before movies were even a thing.2

Art Isn’t…

Okay, the computer isn’t an artist, but a human being entered the prompt into the image generator. Isn’t that art? Nope.

As the great novelist

put it:Density of microdecisions correlates with good art. A sculpture seems more marvelous to us when we consider the number of times the sculptor had to strike a chisel with a mallet in order to fashion it from a block of marble. But that alone doesn’t assure success; those microdecisions have to have been made in accordance with some kind of overarching plan for what the finished work is going to look like.

Each artform has its own set of conventions and constraints. For example, if I’m writing a sentence, I can choose from any word in the dictionary. But once I’ve made that choice I need to spell it correctly or else no one will be able to read what I’ve written. And there is a vast range of ideas that I could express in a sentence, but the sentence needs to be structured according to rules of grammar.

Notwithstanding all of those rules and constraints, there is still vast scope of possible things that a writer can say. Moment-to-moment decision-making is happening in some kind of intermediate zone between—at the more granular level—spelling words correctly (where there is only one correct choice) and writing grammatical sentences (more choices, but still somewhat rule-bound) versus—at the higher end—delivering a coherent manuscript hundreds of pages long.

That intermediate zone, where all of the decisions get made, is poorly understood by non-writers. Many published novelists, including myself, have stories about being approached by someone who “has an idea for a book” and who proposes that the writer should actually do all of the writing and then split the proceeds with the idea haver.

What idea havers don’t understand is that it’s in the making of all of the microdecisions that the actual work of creation takes place, and that without it the idea might as well not exist. Someone could approach Leonardo da Vinci and say “I have an idea for a picture of a woman sitting in a chair smiling enigmatically” but it would be worthless compared to the finished work, which is realized in the form of countless individual brushstrokes, each reflecting a microdecision on the part of the painter.

Okay, that pull quote is long enough as it is. I recommend reading the whole thing—

Appreciating Inhumanity

So AI images aren’t “art” in the sense of an artist conveying something to an audience, but we can still appreciate it, right? There’s beauty in a sunset, or a flower, or drops of rain, none made by human hands.

Possibly. The audience doesn’t really care how something is made, generally. There may be some bias against AI generated “art” at the moment, but surely that will fade away as the generations pass.

In fact, the bias may disappear when the audience doesn’t know an image was AI-generated.

has posted some fascinating results to an image-based Turing Test.Already Imminent

When I’m writing, I sometimes listen to Catholic chant or choral music on YouTube. Usually, they’re accompanied by cute little cartoony animations, like this one—

But other times I find images like this—

Less sacrilegious but somehow more horrifying is this video, made for children, that seems to be entirely AI-generated, from the images to the animation, to the text and voice. The images are quite literally disgusting, but the story is simply incoherent. Every sentence makes sense in isolation, but nothing relates to anything else. AI just isn’t capable of writing a script, because it doesn’t know what a story is. As

put it:3 A story told by GPT-3 is quite literally a tale told by an idiot, signifying nothing.What I’m getting at is, the future is already here. Even if it’s not yet Hollywood-level, people are making money off this technology (or at least trying to). The advances in both text and image-generating AI have been impressive lately, and they’ll only get better.

Right?

Already Inert

Maybe technology will improve to the point that we won’t be able to tell human-made art from AI-generated images. But maybe not. It’s entirely possible that AI has simply hit a new plateau. They’re fun toys to play with now, but once the novelty wears off and the idea of using nuclear reactors to create Detective Dinosaur?™

The lack of any semiotic understanding is a roadblock for both image and text generation. AI literally loses the plot almost immediately. Faster processing and more tightly woven neural networks won’t solve that problem. AI is already faster than the human mind and has more ready access to a larger store of information.

But it doesn’t understand any of it. It’s a difference in kind, not degree. As Noam Chomsky put it, “Asking if a computer can think is like asking if a submarine can swim.”

Lord knows I’m not a fan of Patrick Willems, but he made a good video about this a while back. Here’s a quick excerpt—

Another Iteration

I saw a really interesting tweet which said something to the effect that, “Hollywood movies won’t be the end state of AI anymore than filmed plays were the end state of the motion picture.” I can’t find the exact tweet, because I can’t remember the specific phrasing (film/movie/motion picture, play/theater/stage), and the AI that powers Google search is looking for word associations and not specific meanings.

Which pretty well sums up what I think of all this. Artificial Intelligence will not, cannot, replace the majority of jobs on a film set. It will likely be used as a tool by many of those crew.

But ultimately, AI won’t be a way to make cheaper movies—Hollywood-level production value by one person typing prompts. What it is going to be is something else, something we can’t imagine any more than a country bumpkin in the 1880s could imagine a moving image on a silver screen.

What do you think?

Which is why I think Fan Theories Suck when they ignore artistic intent.

It’s one thing to get movie trivia wrong, but apparently, AI hallucinations bullshit has made it’s way into legal cases.

Paraphrasing Shakespeare, obviously.

Good articulation of the limits of AI. Meaning is the secret ingredient in the sauce.