Why Does Disney Hate Its Own Brand?

The only Disney article you'll read this week that's NOT about 'Snow White'

I promise, this isn’t another post about Snow White. As a film, it’s beneath our consideration.1 But regardless of the quality of that movie and any controversy surrounding it, I concede that, conceptually, it makes sense as a business proposition. A bad movie isn’t good for the Disney brand, but at least a princess remake is (theoretically) on brand, which is more than I can say for the Hot MILFs in Ur Area billboards I’ve seen all over town for the last month—

But I’m getting ahead of myself…

Ed. note: This post is way longer than I intended, so it may be truncated in your email. Click through to the app or website to read the whole thing. Including the footnotes! (Which I just learned some people don’t read until the end.)

One Brand to Rule Them All

Most major studios don't have a brand, in the eyes of the public. Occasionally, a smaller company gains a reputation amongst a niche audience—A24 stands for a kind of quality arthouse film, Blumhouse (usually) means low-budget horror, that sort of thing. But ask a random person on the street, “What's the difference between a Universal picture and a Paramount film?”, and all you'll get is a blank look.

The exception is Disney.

For generations, Disney stood for family entertainment. They made films that were appropriate for kids, but adults could enjoy as well. Classic fairy tales, adventure stories, silly cartoons, even nature documentaries—not childish, but full of child-like wonder.

Naturally, the meaning of “family entertainment” has certainly evolved over the years. At the climax of Fantasia (1940), Satan2 himself is frightened away by nuns singing the Ave Maria. Sixty years later, Fantasia 2000 ends with a generic lava monster and then some sort of nature spirit healing the forest with the power of environmentalism or something.

Though even as public tastes changed, Disney was still Disney.

Acquisitions and Expansion

In the 1980s, the studio was floundering, even and especially its animation division. So Ron Miller, son-in-law of Walt Disney and the last CEO to have a personal relationship with Walt, founded Touchstone Pictures. Wholly owned by Disney, but without any branding to associate it with the parent company, Touchstone was able to release PG-13 and even R-rated movies without besmirching the good Disney name. It worked quite well for decades.

People don’t remember it now, but Disney also owned Miramax (and its horror subsidiary Dimension Films) from 1993 to 2010. Which means Disney (through its Buena Vista distribution company) released movies like Pulp Fiction, Scream, and Shakespeare in Love. But due to layers of corporate ownership, nobody thinks of those as Disney movies. They had no effect on the brand.

Thus, when the animation studio bounced back with four classics in a row3 (Little Mermaid,4 Beauty and the Beast,5 Aladdin,6 and The Lion King7—watch the great documentary Waking Sleeping Beauty for details), the public didn’t have to reassess their understanding of what makes a Disney movie a Disney movie. This was a renaissance, unrelated to the 90s indie boom led by Miramax.

Around the same time Disney’s animation quality started to drop off, Pixar burst onto the scene. Disney distributed their computer-animated films openly, and brought the characters into the Disney parks. For a decade and a half, Pixar created an unbroken string of beloved films.

Disney distributed the first six films, then outright bought Pixar in 2006. But in the public’s mind, the best8 animated family films were all Disney.

For the first 90ish years, Disney maintained its family-friendly brand. Then, something happened in the 2010s…

Ladies and Gentlemen, Boys and Girls…

Thanks to princess films, Disney pretty much had a lock on the young (and not-so-young) girl demographic. The Pirates of the Caribbean series, based on a Disneyland ride, had performed well with boys, and CEO Bob Iger felt the studio needed to expand into that market. Since acquisitions had done so well in the past, it made sense when Iger oversaw the purchases of both Marvel Entertainment in 2009, and Lucasfilm (i.e. Star Wars) in 2012. Both brands were incredibly popular with adolescent boys, as well as the public at large.

Despite the explicit goal of targeting male youth, Lucasfilm almost immediately focused the majority of its output on female-led projects. Marvel’s pivot wasn’t quite as sudden or dramatic, but post-Endgame, they’ve noticeably increased the number of female superheroes.

At the same time, Disney’s traditionally female-skewed projects have changed as well. One noticeable aspect of the newest crop of princess movies is the shift away from romance. Disney has also made an effort to de-sexualize (or de-objectify, if you prefer) female characters in the parks. Jessica Rabbit was covered up in the Roger Rabbit ride, and redressed like Dick Tracey—

Tinker Bell no longer has a meet-and-greet at Disneyland or Disney World, because she was deemed “problematic” by the Stories Matter initiative. As quoted in the New York Times:

According to two current Disney executives, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss confidential information… Tinker Bell was marked for caution because she is “body conscious” and jealous of Peter Pan’s attention, according to the executives.

Whether these changes are “too woke” or simply keeping up with modern sensibilities, I leave to you to decide. But in Disney’s defense, at least it seems they are trying, in their very corporate way, to stay on brand for what’s appropriate for children.

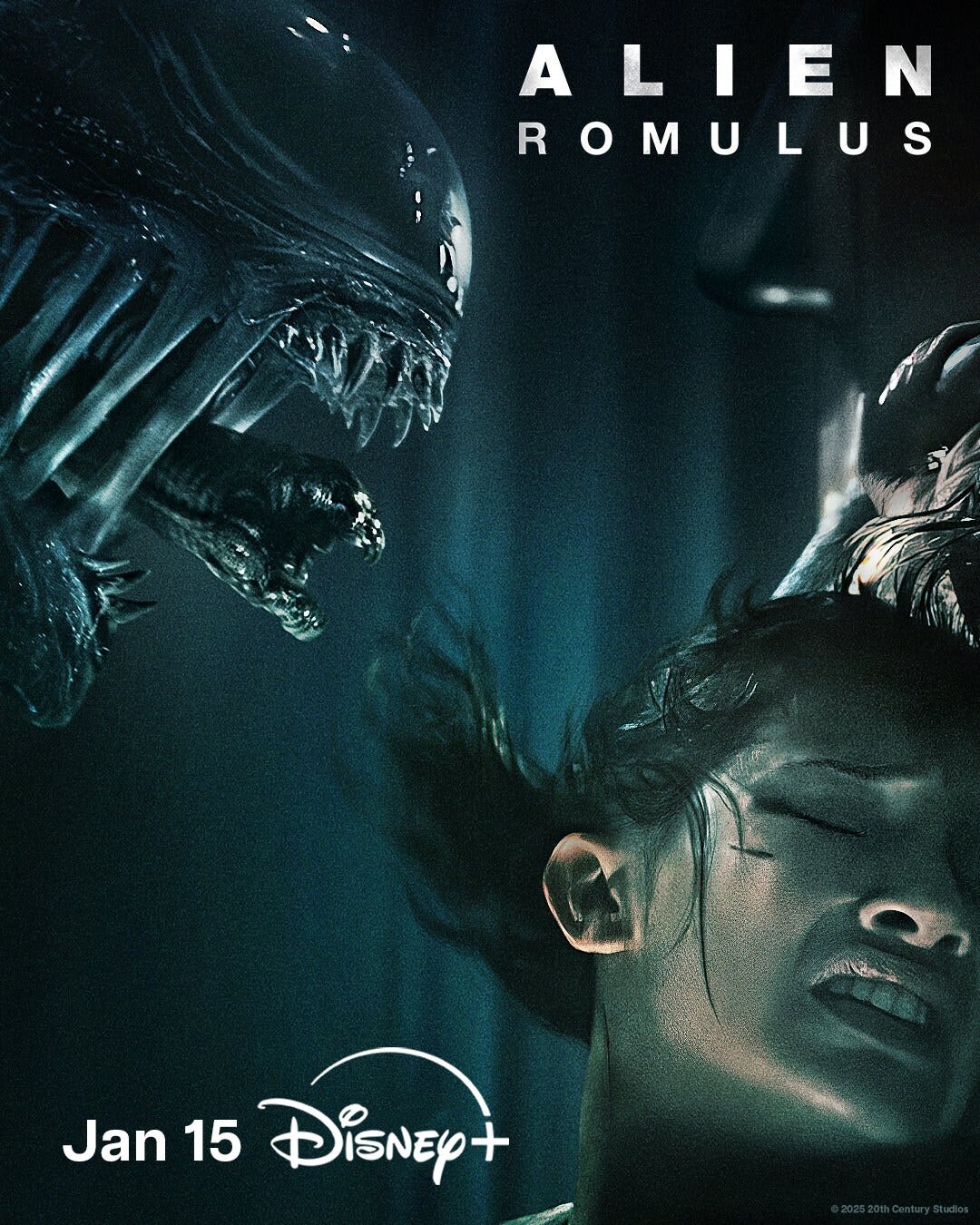

So why does this poster for Alien Romulus have a Disney+ logo on it?

Streaming Everything

Listen, I liked Alien Romulus. I like the whole Alien series, including the games. Interestingly, Disney has had a longer relationship with Alien than even Star Wars. It was featured in a scene on the Great Movie Ride (RIP the best ride at Disney’s Hollywood Studios). There was even a whole stand-alone attraction that began as an Alien tie-in at Magic Kingdom.

But the Great Movie Ride was designed to cover the whole history of cinema, not just Disney movies. And ExtraTERRORestrial Alien Encounter was changed into a Lilo & Stitch attraction specifically because it was too scary for Disney.

So why does the Disney+ landing page have the xenomorph looming over Mickey Mouse’s Funhouse?

To clarify, I’m not complaining about kids having access to adult content.9 That’s up to the parents to control. I’m merely talking about the brand that the Disney corporation uses to present itself to the world.

Edit 3/31: Based on some of the replies, I want to emphasize the point that this piece is not about what children have access to. (Although maybe it’s worth noting that certain children’s classics—like Fantasia and Peter Pan are not accessible on kids’ accounts, and the Dying for Sex and Alien Romulus billboards prominently featuring the Disney+ logo are all over Los Angeles and impossible to miss on a commute.)

The actual question at hand doesn’t change whether kids see these productions or only adults. They undermine brand regardless.

After adding Fox to its ridiculously large conglomerate in 2019, Disney owns a huge amount of intellectual property: Mickey Mouse, Alien, Planet of the Apes, Avatar, Simpsons, Star Wars, Spider-Man, Iron Man, Avengers, Frozen, The Muppets, Winnie the Pooh, Toy Story, X-Men, National Geographic, ESPN, ABC, Star, Sky, Hulu… It just goes on and on.

That’s not a “brand.” That’s just a big pile of IP. What does Luke Skywalker have to do with Kermit the Frog?

Instead of trying to maintain the “family entertainment” brand, Disney decided to just throw everything onto the same streaming platform. This, despite the fact that, after purchasing Fox, they now own controlling stakes in two streaming platforms—Disney+ and Hulu. They could’ve easily separated the two brands, maintaining Disney’s family-friendly image and moving all the “adult” stuff to Hulu. Instead, they gave us these—

The question is…

The Very Dumb Answer

The Disney brand has had value for a century. Both Star Wars and the MCU are generational brands, but Disney was inter-generational.

Fans pass their love for princesses on to their children. They buy Mickey Mouse dolls for their grandchildren. Parents plan for Disneyland/World/etc, because they can be confident that it’ll be fun (and appropriate) for the whole family.

But if Disney continues on their current trajectory, their brand will become “everything,” which in effect means nothing. It’ll be Netflix, only worse.

So why are they doing this? I think somewhere in the deep recesses of their black hearts, every studio executive wants to be “the” entertainment company. For a while, "Netflix" and "streaming" were synonymous. It's not that way anymore, and it never will be again. Disney believes if they own premium television like the FX network, and children’s animation, and superheroes, and and and… we’ll give in and subscribe to Disney+ as the everything store.

The thing is, every major studio (plus Amazon and Apple) started their own service. No one's going to subscribe to them all, but the inverse is also true—no one's going to subscribe to just one, no matter how much intellectual property they own. I still want to watch Superman, and SpongeBob, and whatever weird French movie Criterion is streaming this month.

Disney is destroying their brand for an impossible dream—to become The (one and only) Entertainment Company. Fifty years from now, will a “Disney movie” be as meaningless as a “Universal picture”? Twenty years from now? Ten? Does Disney mean anything to my daughter other than the place to watch Bluey, which Disney doesn’t even own?

What do you think? Is Disney killing it’s own brand? Is it too late to save it?

Although the Man Carrying Thing meta-commentary is funny, and well worth the 65 seconds it takes to watch.

I know later ancillary materials from Disney officially call him “Chernabog,” but in the movie itself, Deems Taylor calls him Satan, and I’m nothing if not a textualist. Besides, Walt identifies the character as “Satan himself” in the classic Disneyland episode, “The Plausible Impossible” (which seems to be only available on Disney+. And you know how I feel about authorial intent.

I don’t care about The Rescues Down Under, and don’t pretend you do, either.

Shrek is overrated. Fight me.

Please note that I’m using the word “content” in the most insulting, demeaning way possible.

Good piece, I also find myself hellishly confused by the overlap between Hulu and Disney+.

I think there is a huge, hidden engines driving a lot of these developments though, which is:

Risk Management.

The upper strata, C-Suite in particular, at most studios, and especially at Disney, is no longer populated by executives that worked their way up either through studio development or through filmmaking physical production. Studios are now mostly run by an entirely separate class of business school trained executives who want to run their studios as traditional corporate businesses.

And movie studios just…don’t work that way. The way they generate revenue is different. The way they deploy capital is different. Their obligations to shareholders are different.

The biggest driver of the issue is that film — any art — is predicated on risk. Creative risk. But traditional business theory wants to eliminate risk. The only way to even try to do that in film is to keep making things that are or are connected to “proven quantities” — aka IP stuff. Which isn’t inherently bad — some IP films are great — but there’s only so long you can do it before you’ve glutted the market. And you also always have to keep doing bigger and better and more star studded versions to pull people back in — so costs spiral out of control.

It also reads on paper to executives as “safer,” to basically make things by committee, sanding off all the rough edges of a singular creative vision in favor of “best practices.” But not only is that approach timid — and leads to the wishy-washiness around cultural issues — it’s also extremely inefficient. Disney could make a lot of their projects for a cool hundred million or so cheaper if they just trusted their directors to cook for them, but they fiddle with everything in post production for so long that the costs go out of control. And then the thing naturally ends up being bad and flopping, and the only way to patch that huge financial hole…is to double down on another IP “sure bet”. So, what you need most of all in this situation…is to hold all the IP you can, because that’s your only safety net.

And thus you have all the acquisitions that have both furthered Disney’s financial issues, diluted its brand, and become a major headache for them because they’re realizing you really can’t please anyone with this nostalgia stuff for long.

Great article, very insightful. Thanks.

My teens have mentioned this to me all on their own and they’re a bit disgusted by it when surfing D+ with their little siblings. It’s a major turn-off. What’s disappointing, I realized as I read your article, is how much of this could have been prevented if Disney took the moral of so many of its own stories.

“Be yourself” may lend itself to woke messaging, but it’s hardly new, reaching back at least as far as Shakespeare. Why do they yield to peer pressure?

“Because when everyone’s super, no one will be.” Syndrome’s line in The Incredibles popped into my head near the end of the article. Why does Disney want to be everything?

Last but not least, my mind went to Ratatouille, whose diminutive chef — I mean the pencil-mustached human, not the rodent — was pimping out his old friend’s name to hock cheap garbage for a quick buck.

Perhaps Disney needs to watch more Disney.