Memory is funny. The strangest things can push a train of thought down tracks whose destination you’d never expect. For example, an article at

by got me thinking about a film I directed nearly a decade ago.What School Didn’t Teach Us: You Need to Lose Control is a well-written article; I recommend reading it.

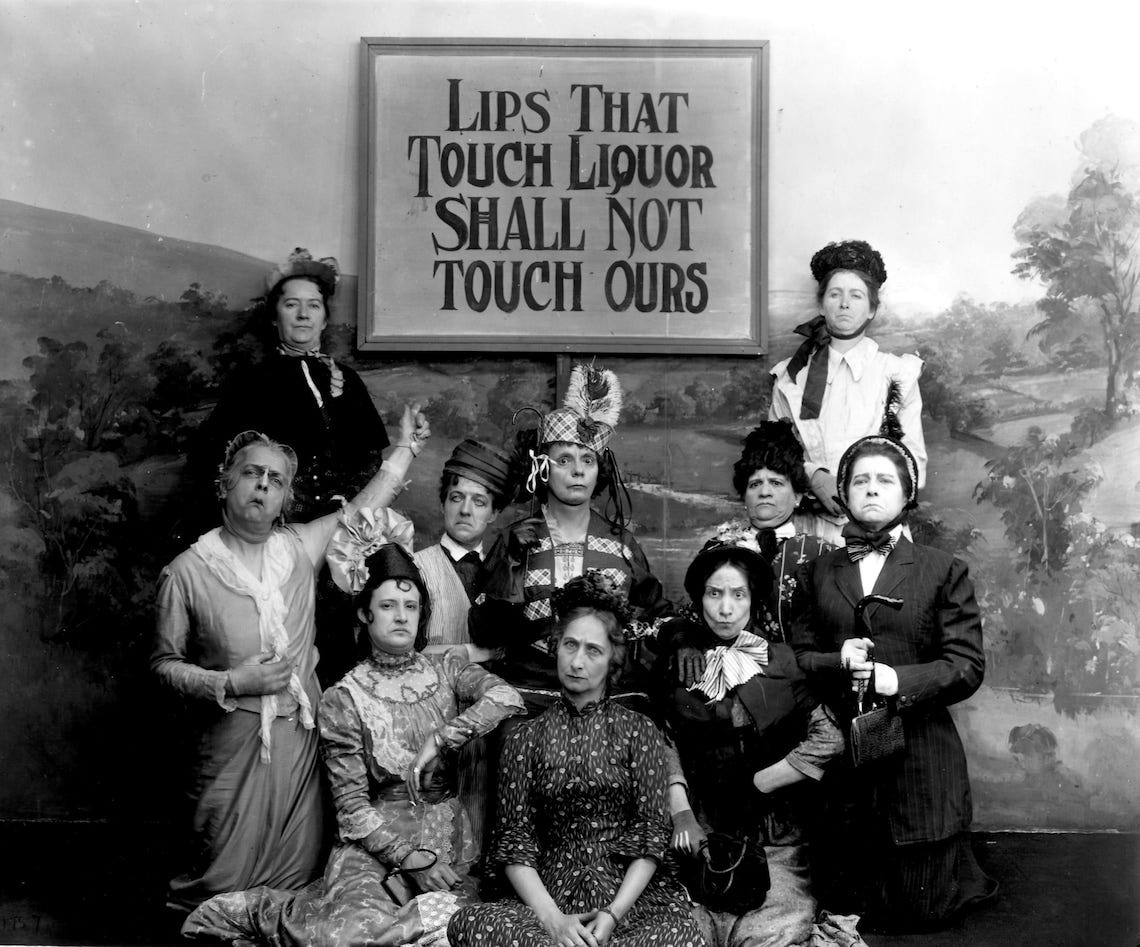

What could be worse to a cohort of anxious perfectionists than the thought of a substance that first and foremost lowers your inhibitions?

And yet, it’s this quality that has always made alcohol such a fundamental part of social life. Drinking makes it easier to be with people, and to be yourself; to talk and dance, tell jokes and stories, flirt, even fall in love.

Also, I disagree with every single word of it.

Self-Control

I think our inhibitions are there for a reason. If you truly have a hang up about personal interactions, that’s something you should probably work on without artificial help.

In fact, I wrote a whole movie to make that point: Other Halves.1 It’s a kind of Jekyll & Hyde story, only instead of an injectable serum that transforms you, it’s an app.2 Here’s the trailer—

As I explained in one of my earliest video essays, every film has a theme, teaches a lesson, makes an argument. Other Halves’ theme is simple: self-control is what makes us human. The heroine, Devon, pretty much spells this out at the climax of the film—

DEVON Without self-control, we're just... animals. JASMINE No, no. That's not the self. It's society telling you you have to look pretty, it's the church telling you you dress like a slut, it's your parents telling you your little sister is better because she got marred when she was 23 and you're still single. Other Halves releases you from all that. It lets you be the real you. DEVON That's bullshit! This is me! (hits her chest) With all of my hang-ups and guilt and propriety and shame. They're just as much a part of me as my base instincts. It's all me.

But anyway, you don’t read TMFS for my teetotaler moralizing.

You want to hear how I made a movie.

Memory Lane

It occurred to me that I haven’t talked about my own (first?) feature film here on TMFS very much.

Other Halves was a micro-budget film (as in, less than $40,000), but I’m still reasonably proud of how it turned out. It doesn’t look like a studio movie, but if I hadn’t just told you how much it cost, you’d probably guess at least ten times that. The cast and crew were great; any flaws in the movie are probably my fault. (But I’ll get to that later in this article.)

Good Bad Flicks made a fun video essay on the making of the movie—

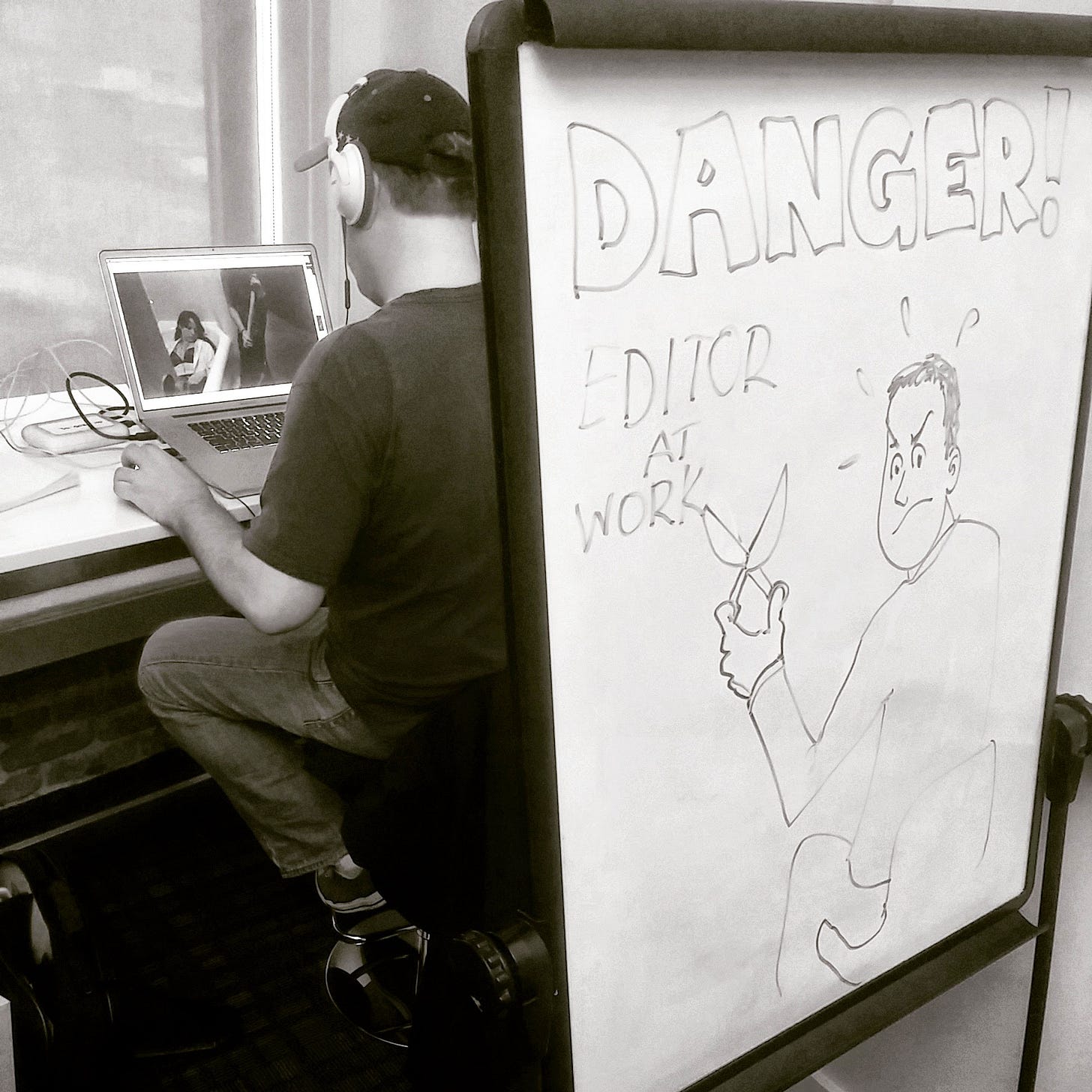

For a more first-person perspective, my friend and editor Don Stroud also recently wrote about working on Other Halves (among many other Hollywood projects). He’s a little overly complimentary of me; I think he’s a great editor with or without my help.

We premiered the movie at ZedFest about nine years ago. My how time flies!

Cool Shots

The initial idea for Other Halves was mine, and I wrote a draft before bringing my friend Kelly Morr in to co-write with me. My friend Curt Chatham found financing, and together we put together a cast and crew to film in San Francisco, where some of my college friends lent us a lovely location. In fact, the movie was kind of written around that location—my friends created a startup, so we made a movie about creating a start up.

That’s the boring stuff. As director Fred Dekker wisely put it:

The ultimate irony is this: even when a story is derivative or trite or incomprehensible, even when it openly insults an audience's intelligence, there is one thing that, now more than ever, the public will respond to and throw their money at again and again:

Cool shots.

So, here are two cool shots from Other Halves that I’m proud of not only for their aesthetic merit, but also the thought process and work that went into creating them.

It’s All About Timing

This first shot is in the middle of a rather long scene.3 In the first half of the scene, Devon (played by Lauren Lakis) is starting to realize that the Other Halves app is affecting her mind and perception. She’s also afraid her friend and business partner, Jasmine (Mercedes Manning), might actually be responsible for the bug in the app that’s causing all the bloody mayhem.

Devon exits, and almost immediately Elle (Lianna Liew) enters the scene. She has also figured out that the app breaks down the user’s inhibitions. The difference is, she likes the feeling, and she’s come to tell Jasmine they ought to keep developing the app in that direction.

Obviously the emotional states of the two characters are radically different, and I wanted the camerawork to reflect that. But I didn't want to just cut from Devon's restrained camera movement to Elle's shaky cam. I needed to connect them in continuous time and space, since they're both responding to the same thing—the app—in diametrically opposing ways.

In order to go from a smooth dolly shot to handheld, I devised a fairly simple, but effective trick. We had a tripod dolly on dolly track, but instead of securely mounting the camera to the tripod head, we simply put a large sandbag on top. When we followed Lauren into the elevator alcove, the DP pressed the camera firmly into the bag. Then, when Lauren cleared frame and Lianna stepped off the elevator, he just lifted the camera up and onto his shoulder, and tracked Lianna through the rest of the take. Another member of the camera team is just out of frame, too; he yanked the tripod out of the way, so it wouldn't accidentally get caught in the shot or trip Lianna up.

The cinematographer said there was no way this shot would work. He insisted it would be obvious the camera wasn't really locked down, and the transition to his shoulder would be too rough. I think he pulled it off masterfully, like I knew he would.

To be clear, I don't actually believe I invented a new kind of shot. I probably saw someone do this on set, or read about it in a class, but I can't for the life of me remember what inspired this shot. That's what happens when you've had too much film school.

Besides the camera, there was also a logistics issue with the elevator. This was filmed in a real location, not a set. If we were on a soundstage, there would just be two guys behind the walls, pulling the doors open and shut.

But this was a real elevator, over which we had no control. We did have permission to film on two floors, and we were shooting at night, so we could at least be reasonably sure no one else would be riding the elevator.

We made due with the control we did have. A production assistant timed how long it took from the moment she pressed the floor button until the elevator doors opened up. Then we walked through the first half of the shot with Lauren, to see how long she needed to reach the stairs. We then subtracted one time from the other.

Once we were rolling, the AD called out "Action elevator!", the PA pressed the floor, and hid in the corner of the elevator. I counted to seven Mississippi, then cued Lauren and the camera. The timing was perfect, and I believe we only did a couple of takes.

Staging in Depth

This shot is less show-offy, for a couple of reasons, and the first reason reflects poorly on me. I had planned out the shots for about 90% of the movie; this shot fell in that final 10%. The whole production, I figured I'd get around to blocking it out, and if not, it was simple enough to just shoot coverage.4

Secondly, this was literally the last shot of principal photography. We had to wrap up and clear out so my friends could have their office back to start work in the morning.5

With no time and no plan, I found myself in that classic film school assignment: filming the entire scene in one setup.6 Luckily, I had been reading a lot of David Bordwell, and thinking in particular about his advocacy for more elaborate staging.7 So, I tried thinking in terms of depth, rather than simply vertical and horizontal composition.

I’m not saying this is Citizen Kane or anything,8 but I am rather proud of how dynamic the shot feels, despite not moving at all.

At first, the viewer’s eye bounces between Lianna and Mercedes in the background, and Lauren in the foreground. (It helps that Lauren is spinning around all goofy. She was given pretty tight marks for just how far she was allowed to twist, without blocking the others.) When Lianna comes forward, she metaphorically takes control of the scene, and you can feel the mood shift from passively observing to actively intervening. Lianna’s gaze controls where we look, deliberately not turning towards Mercedes when she’s speaking. Finally, she walks back to the background, and we’re drawn in without even a slight push in.

All of that would’ve been lost if there was cut in to a close-up.

A Bad Shot

82 seconds isn’t a record-breaker or anything, but it’s 30 times as long as the average shot in a modern movie. Don and I both tend to favor longer takes,9 but much of our footage couldn’t really sustain that.

Take this shot, for example, from an early scene where we’re still meeting the whole cast of characters—

All of the action is over on the left side of frame, with Devon and Mike (Carson Nicely). Jana (Melanie Friedrich) is squished over on the far right, not really doing anything for much of the scene.

We were supposed to be able to see Jasmine in her office (and you can technically see her legs, if you look hard), but she’s not doing anything interesting either. Three-quarters of the frame is just dead space. Are supposed to be looking at the plant? The candles?

What I’m talking about here, to use the fancy film school word, is mise en scène. It’s not the production designer’s fault (the set looks good), nor the camera operator’s (he framed it how I told him to). The actors played the scene; they have no control over how they look in the shot.

That’s the director’s job. That was my job.

I should’ve brought the characters closer together, and tightened the shot. More importantly, I should’ve given Mercedes (playing the villain) something ominous to do in the background. The contrast between the above shot and the two previous ones is striking. I hope I’ve learned my lesson.

Teamwork Makes the Dreamwork

Everything I’ve described up to this point is really just a small part of what it takes to create a shot. We had to hire the crew, buy and fit costumes, dress the set, do hair and make-up (including blood effects), cast the movie, rehearse, light the scene, get everyone and everything to and from San Francisco. That’s just production. In post, there’s editing, color timing, sound mixing, scoring.

Take the second scene, which is a flashback. That weird sounds you hear at the beginning and end are a collaboration between our composer Erick Del Aguila and sound designer Chris Henry. Erick wrote some two second clips of the Other Halves theme, and Chris mixed that with stabbing sounds and computerized effects. The end result is pretty creepy, I think.

As a director, I’m proud of these two shots. I’m also proud of the cast and crew who made these two shots possible.

Thanks for taking this long trip down memory lane with me. I’ll talk about other people’s movies again next time, promise.

As of this publication, you can watch it for free on Fandango, as well as buy it on YouTube. Normally, I would link to Amazon, but the version on Prime is censored, as is the free stream on Plex. How our distributor decided who got which version, I have no idea.

The tagline on one of the posters was “It’s a killer app,” which led some dumb reviewer to infer we started with that line and worked backwards. In fact, the opposite is true. The initial idea was simply an injection, until we decided that was too much of a 19th century concept.

In fact, it was scripted as three scenes, because the elevator foyer was a “different” location. This confused the UPM, who originally scheduled all three parts on separate days.

Meaning I could get a wide shot, then close-ups of each character, and worry about cutting it together in post.

They lent me the space for 8 days, and we shot 2 more at other locations for flashbacks. In total, we filmed for ten days, plus a day of pickups in Los Angeles.

We had three-to-four cameras going for much of the shoot. The cinematographer hated it, and the editor loved it. At this point, however, the camera crew were wrapping up whatever they could. I think we had a B-camera rolling on a two-shot of Jasmine and Elle in the background, but we didn’t end up using it.

His famous Modest Virtuosity post didn’t come out until after Other Halves’ festival premiere, unfortunately.

We didn’t have enough lights to create deep focus, for one thing.

The Spielberg Oner was also on my mind a lot at the time.