Taking Notes from the Audience

On the History and Practice of Test Screenings

Last time, I talked about how you can get into a test screening as an audience member. But one has to wonder, what’s in it for the filmmakers to show their movie early? And for free, to boot!

Some people might say it’s because the studio wants to dumb it down to the lowest common denominator. But that’s not true. (Mostly.) There are a lot of good, sound, artistic reasons for showing your film to a small group of people before finalizing it.

Older Than You Think

Market testing seems like a relatively recent development, but studios and filmmakers have been doing it for a while. A test screening features prominently in Vincente Minnelli’s 1952 classic movie about movies, The Bad and the Beautiful. Kirk Douglas plays Jonathan Shields, an up-and-coming producer who’s just finished his first solo effort.

In reality, test screenings are even older than that. In the previous post, I mentioned David O. Selznick previewing Gone with the Wind, but he’s not the only classic-era producer to do so. Samuel Goldwyn1 changed the ending of Wuthering Heights due to audience feedback. Irving Thalberg (for whom the lifetime achievement Oscar is named) tested, re-shot, and re-cut films incessantly such that his studio was known as “retake valley.” Thomas Schatz, in The Genius of the System, records Thalberg previewing and re-cutting a The Big Parade, a film made in 1925.

The postproduction work also confirmed what was emerging as one of Thalberg’s basic tenets of studio filmmaking — namely, that the first cut of any picture was no more than the raw material of the finished product.

This preview- retake process was indeed extravagant, and no other studio adhered to it as a matter of policy… But Thalberg figured that the public was the ultimate arbiter of a movie’s quality, that only an audience could decide if a picture really worked.

This wasn’t just limited to producers and executives. All of the great silent comedians, from Chaplin to Keaton,2 fine-tuned their comedies before releasing them to the public, but Harold Lloyd may have been the first filmmaker to do so. He said in an interview with Film Comment:3

You finally got to know, by trial and error — you began to find out pretty well what you know is funny and what is not funny. But that’s a long way from being a sure method. I was one of the first ones — I have been given credit for starting what they call “previews.” Even back in the one-reel days, I would take a picture out to a theater when I knew the picture wasn’t right. I wanted to get John and Mary’s opinion of it. And the manager used to always have to come out and explain what was going on. When we were doing two-reelers, he came out in white tie and tails to do it, and it was quite an event for him and the audience would listen attentively. The audience didn’t know what “previews” were, but there’s nothing like an audience to tell you where you go wrong.

So “previews” were one of the best methods we had and, I think, it saved us a great deal of — not that we didn’t go off the track many times in spite of it—but it saved us many times because we would find out that certain sequences were splendid and others weren’t.

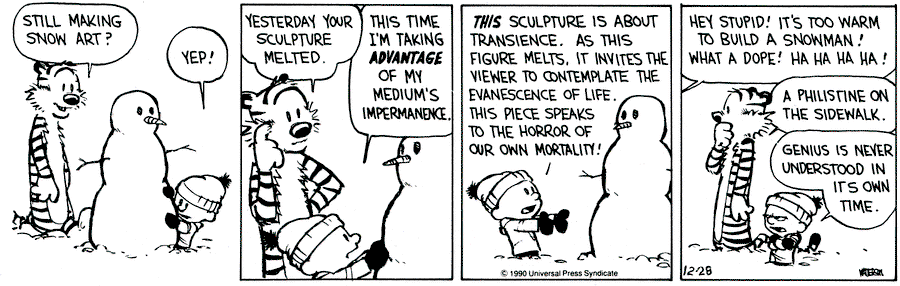

Comedy is Hard

You might wonder why something as (pseudo) scientific as audience testing started with something as subjective as comedy. It comes down to something Jon Stewart once said: comedy is difficult because you know for certain whether you got it right or not. People laugh or they don’t. It’s pass/fail.

As quoted in Cut to the Monkey, editor Ivan Ladizinsky said he never listens to one person’s opinion. “But if three people tell me something’s wrong, they’re always right.” Curb Your Enthusiasm editor Steven Rasch is quoted in the same book: “Even though you think you know where the laughs are, I’ve been doing this for thirty years and it’s always a surprise when you bring people in the room and hit play.”

There’s always the possibility that something is funny to the writers/editor/producers, but not to anyone else. Rob Long describes a “room run”—basically, an inside joke from the writers room that doesn’t make sense to anyone else.

Plus there’s a danger that the premise of a joke is too obscure for the general audience. I worked on a sitcom that featured John McEnroe as a guest. In a running gag for the episode, all of the regular characters kept expecting him to explode with anger, but he never did.

The problem was, no one in the live audience had any idea who McEnroe was, and had no expectation for his temperament, so the jokes fell flat every time. One of the writers was absolutely livid that they had to add exposition about a world-famous tennis player…who had retired decades earlier, while most of the target audience were children.

Testing a film (or show) means not being stuck in your own head.

Make it Make Sense

Testing doesn’t just reveal problems with specific moments, like jokes or scares. Sometimes the overall tone of a film can unintentionally confuse the audience, when not set up properly.

La La Land is a musical. You probably know that. The filmmakers knew it. The studio knew it. The research company knew it. Do you know he didn’t know it was a musical? The first audiences.

In the first cut of La La Land, the movie started out like any other romantic comedy. We meet the two leads, a couple of side characters, learn about their struggles, and then twelve minutes in, they start singing out of nowhere…

The audience was baffled. It took them a while to figure out what the heck was going on, and by the time they caught up, they were out of the movie. They were focused on their confusion instead of the story.

Luckily, the filmmakers had accidentally already created the solution. They shot a dance number on a real LA freeway, but subsequently cut it because it wasn’t, strictly speaking, necessary for the story.

But it sure as heck was necessary now! They took the musical number “Another Day of Sun” and plopped it down at the start of the film. Suddenly, with almost no other changes, preview audiences loved it. It had nothing to do with plot or character, but style, and it saved the movie.4

Don’t See It Alone

Watching a movie in a theater is a communal experience. Some movies just don’t work as well alone. Comedies are like that, and horror movies, too.

Paranormal Activity had had some success on the festival circuit, and the film had been picked up as a straight-to DVD release. Director Oren Peli’s agents showed the film to producers as a directing sample.

Jason Blum was blown away. He knew the movie could be a hit. He believed in it so much that bought the rights away from the video distributor so he could convince Paramount (who he had an overall deal with) to release it theatrically. But the studio executives didn’t have his vision.

Blum had an ace up his sleeve. He could arrange a test screening, which the executives would have to attend. When the audience proved Blum’s intuition correct, Paramount did a complete 180 and made Paranormal one of the biggest horror franchises of the 2010s.

“Until you screen it in front of strangers and feel what it feels like to be in that theater with those strangers, you have no perspective on your movie,” said Blum. “I knew it would work theatrically, but I didn’t think that there would be five fucking sequels.”

Where’s the Cynicism?

A lot of the above anecdotes come from Kevin Goetz’s Audience-ology: How Moviegoers Shape the Films We Love. As the founder and CEO of Screen Engine/ASI, he’s obviously a biased source. I’m sure there are plenty of times studios ruined an artist’s vision because they were short-sighted, petty, philistines.

But reading his book, you really do get the sense that Goetz wants to help the filmmaker create the best film possible. If you’re making a comedy, you want the audience to laugh; a horror flick, scream; a melodrama, moved to tears.

And to be perfectly honest, while you can improve (or damage) a film quite a lot in post-production, it still pretty much is what it is. Without the proper “raw material” Irving Thalberg referred to, you can very rarely change a film.

But you can change the way you present it.

The Best, Worst Marketing Executive

Some of the most useful information, from a financial point of view, to come out of a test screening isn’t how to improve the movie per se, but to refine the advertising. Those questionnaires and focus groups tell the marketing department which elements of a film to focus on.

I once knew an executive who oversaw all the trailers at a major studio. Billboards, posters, cast interviews—these all contribute to the general awareness of an upcoming movie. But the centerpiece to any movie marketing campaign is the trailer.

This executive told me that most movies are built on a standard structure, given their genre, and thus most trailers for said genre fit a pattern, whether it’s a big blockbuster…

…or Oscar bait.

That covers 95% of his job, but for the remaining 5%, he told me he found joy in two things: “When I get a movie that’s really special, I mean something truly unique, a little gem of a film that I just know people will love if they’d only give it a chance, but it doesn’t have an obvious hook or a gimmick to draw attention? If I can convince the audience to come out to the theater anyway and share in that experience. Man, those times, I can really be proud of my work.”

“What’s the other thing?” I naively asked.

“When I get a real piece of shit and trick people into buying a ticket anyway.”

I think about that guy a lot.

The G of MGM Studios.

Tragically, a scene from Buster Keaton’s The Navigator has been lost to time due to testing. According to Kevin Goetz, he “filmed an elaborate underwater sequence in which he played a traffic cop directing schools of fish, a highly unusual production feat in 1924. When he screened it and moviegoers were too flabbergasted to laugh, Keaton scrapped the entire scene.” But that’s what happened in the day before film preservation.

As an aside, a similar thing happened on my (much smaller, much less successful) film Other Halves, but I’ll save that story for another post.