Framing Aspect Ratios

A brief history

I’ve been experimenting with YouTube Shorts on the Too Much Film School channel lately.1 Some were original videos, while others I clipped from my longer video essays, just to see how The Algorithm™ reacted.

I don’t think I learned anything useful about YouTube,2 but I did notice some interesting things about shot composition and aspect ratios.

This was originally supposed to be a single article, but I got carried away, so I wound up splitting it in two. This first part is a brief history of changing aspect ratios; the second part will pertain to aspect ratios in our modern, mobile world.

Snakes and Funerals

“Aspect ratio” is simply the ratio of the width to the height of the frame. Old films tend to be 4:3, or the Academy Ratio of 1.375:1—

After the mid-1910s, filmmakers relied heavily on close views—framing typically two or three people, or even just one. These “portrait” framings were well-suited to the 4:3 format that was standardized in the silent era. […] The human body, and even a tight facial close-up could fill it fairly well. But a single or even a two-shot, in anamorphic widescreen, can leave a lot of the frame vacant or relatively unimportant.

- David Bordwell, Off-center: MAD MAX’s headroom

I explored this idea—that certain aspect ratios were better for different numbers of on-screen characters—in my short film “Danse Macabre.” It’s about a dancer whose husband has passed away, and she’s decided to find a new partner. As she dances alone, we filmed it in the classic Academy Ratio, but once she begins dancing with her new mate, the screen widens out to 16:9. [NSFW warning: there’s enough sex and violence that YouTube won’t let me embed the video.]

While I changed aspect ratio to reflect the protagonist’s emotional state, this trick is more often used to convey different time periods (à la Grand Budapest Hotel), or to indicate something really cool is about to happen (like when the krayt dragon attacks in The Mandalorian). WandaVision kinda did both.

Widescreen came about as a response to the proliferation of television in the 50s and 60s. David Bordwell has a great video lecture3 on how this affected the way directors staged the actors and cinematographers framed the shots for Cinemascope.

Bordwell is obviously a fan of ‘scope, but you know what Fritz Lang4 said—

So while not everyone agreed, the general consensus was that 4:3 meant either “old” or “television,” while 16:9 (or wider) implied “cinematic.”

Fast-forward to today when most TV’s are widescreen, and now that’s become the standard for almost everything we watch. The general audience seem to think this is the only correct way5 to film something—

But as illustrated in my earlier examples, the “correct” aspect ratio is the one that the filmmakers chose—

Cutting off the sides (or the top and bottom) of a shot is a lot like removing the adjectives from a sentence. Yes, it’s comprehensible, but it’s not as complete.

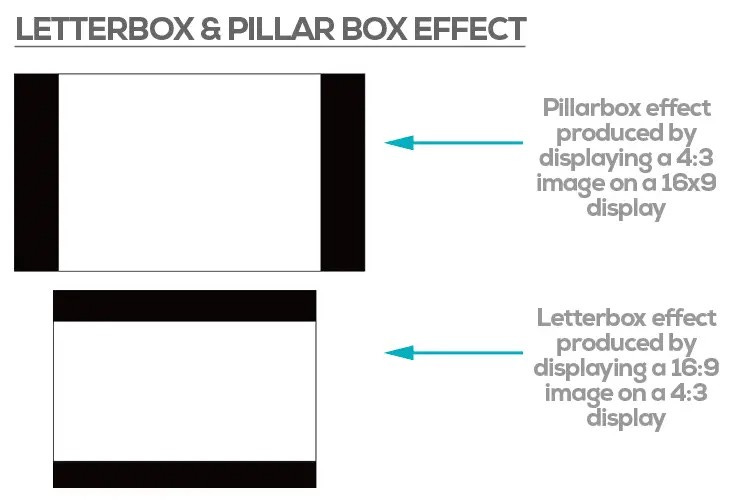

We shouldn’t crop square frames to fit our rectangular flatscreens today, any more than we should have cropped widescreen movies to fit our CRT TVs back in the 80s. Letterboxing (black bars on the top and bottom) and pillarboxing (bars on the side) are the appropriate solutions for persevering the filmmakers’ vision.

Another Perspective

Now forget I said all that.

In terms of exhibition/broadcasting, the impulse behind pan-and-scan approaches the issue from the opposite direction as letterboxing. Instead of considering the creator’s intent paramount, reformatting to fit the screen focuses on the audience’s experience.

It wasn’t just ignorance that led people to prefer cropped images for their home viewing. TV’s used to smaller, and wasting screen real estate with black bars meant the image was even smaller.6

Many directors, throughout the 80s and 90s, began composing shots that emphasized center-framing (which had other advantages, as well). When the film was cropped, nothing important was lost. Some directors ignored the aftermarket entirely, meaning their film would be butchered—

Others chose to shoot on super 35 film, which used more of the film strip for each frame. There were a few advantages to this, in addition to slightly higher resolution.

First, it allowed the director to re-frame shots in post production, if the composition wasn’t exactly to his liking during principle photography.7 Almost as import, when the movie was broadcast on television, instead of cropping part of the shot, the frame was merely expanded—

This was called “open matte,” because the widescreen framing was accomplished by matting out part of the frame (as opposed to Cinemascope and other anamorphic formats, which achieved wider frames with special lenses that “squished” the image.)

Just as a quick aside, anamorphic lenses cause those curious horizontal lens flares that you see sometimes.8

Who’s in Control?

It may sound like when shooting in Super 35, the director concedes a lot of control to the exhibitor or broadcaster, who decides whether the movie will be seen in widescreen or 4:3. Yet, many great filmmakers choose to shoot this way.

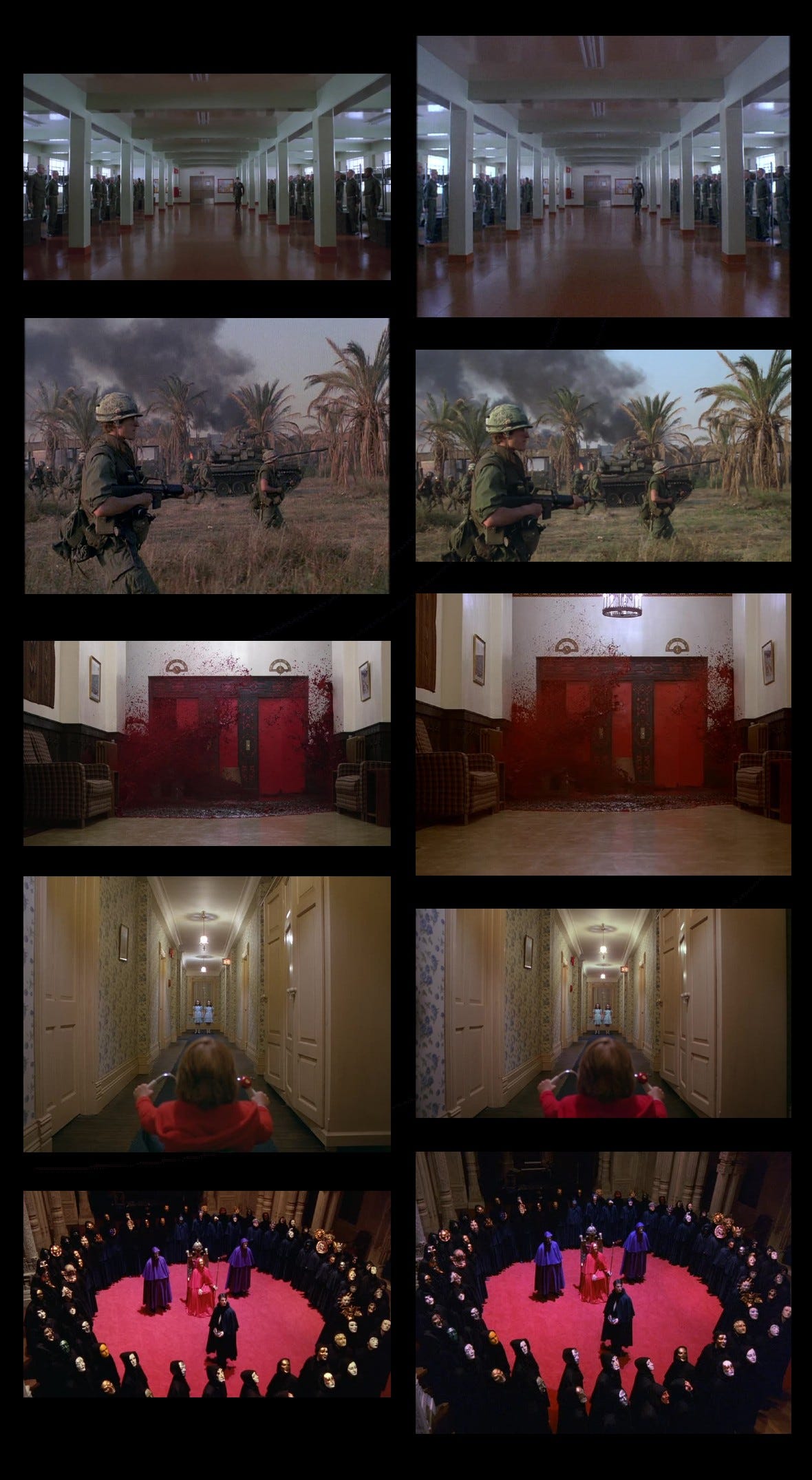

James Cameron shot many of his films on Super 35, including Titanic. Sam Raimi filmed all three Spiders-Men with the format, too. Neither are known for sloppy compositions. Even the most fastidious director of all time, Stanley Kubrick, shot with an open matte.

In fact, since his death in 1999, many people have debated whether Kubrick “intended” his films to be screened in widescreen or square formats.

As you can see, most of these shots work in both framings, although you might prefer one to the other.

But how far can you take this?

Come back tomorrow to find out!

I assume you’re already subscribed, but if not, you should subscribe.

Actually, that’s not entirely true. I learned how to create thumbnails for Shorts, which is needlessly complicated and kinda boring. But at least the thumbnail for the Jessica Rabbit video doesn’t look like the one YouTube generated—

I hesitate to say “video essay,” because it was recorded long before the techniques and tropes of the video essay as such became truly common.

Or possibly Orson Welles. Who knows?

I’ve heard a theory that our binocular vision creates a 16x9 aspect ratio, although I've never saw any proof of that.

This’ll be important later.

I actually had to do this a few times in my movie Other Halves. Although the chips on our cameras recorded natively in 16:9, we framed for 2.37:1, because I’m a big fan of John Carpenter.

Although now, people can add them in post, just to get that “cinematic” look.