I have a sort of dilettantish interest in linguistics, mostly due to my wife’s accent.1 There’s nothing like hearing someone else’s strange pronunciations to make you notice your own.

Take the word “later.” My wife says, “lay-tuh,” dropping the r at the end. You might think we Americans pronounce it more correctly, enunciating every letter, but we don’t. We just mispronounce it differently—”lay-dur,” turning the t into a d.

Normally, none of these random linguistical thoughts would have anything to do with Too Much Film School, but just the other day, I saw this video from Dr Geoff Lindsey. It’s about Hollywood history as much as language, so I think you’ll find it as fascinating as I did—

Print the Legend

Lindsey is absolutely right about how pervasive this folk history is, even in prestigious film schools. I learned about the “fake” mid-Atlantic accent at USC, and regretfully believed my professors.

Cinema is a relatively new art form, so you might think it’s easy to sort real history from fake. By their nature, filmmakers tend to record a lot, and so primary sources are available not only in written form, but also with video and audio of the participants.

But filmmakers are also storytellers, and further, self-promoters. Which is why some myths persist—like the first film audiences being afraid of a train coming off the screen and into the theater. It’s not true (which I’ll address further down in this article), but it’s a good story, so it gets repeated.

Remember, Hollywood is in the west—

I ran into this issue recently while researching my next video.2 It’s a story about trick photography, featuring the Lumière brothers, Georges Méliès, and Martin Scorsese, Reddit, YouTube, and Wikipedia. So read on as I explore movie history and come to a very unsatisfying conclusion.

Hedging History

I do a lot of research for my videos, and one thing I’ve learned is that it’s almost impossible to find the “first” anything. Every time you think you’ve found the first jump cut or the first use of color, you’ll eventually discover that somebody, somewhere else in the world did it six months earlier.

Which is why you’ll hear me couch these kinds of claims with hedge words like, “probably” or “likely.” I know if I definitively say , “This is the first time a filmmaker did X,” someone in the comments will pop in with an obscure Scandinavian film that beat them to the punch.

The one exception seems to be my upside down video; no one has found an earlier instance than When Clouds Roll By.

Time Lapse Collapse

Iconauta is a wonderful resource for looking up silent films. I found what appears to be the very first time lapse photography on their channel—

As I often do with these sorts of things, I shared it on Reddit, under the heading Probably the First Time Lapse in Film History--The Demolition of the Star Theater (1901). Notice the word “probably.” I trusted Iconauta’s description, which claimed it was the first time lapse, but I also had done zero research on my own.

Yet it seems some people don’t take uncertainty as a sign of humility, but rather of laziness—

You know you can look this stuff up right? Carrefour De L'Opera 1897 was the first feature film to use time-lapse.

I admit the condescending tone riled me. And so I fell down a rabbit hole that demonstrated more the flaws of Wikipedia than anything about time lapse films.

Weak Sauce Source

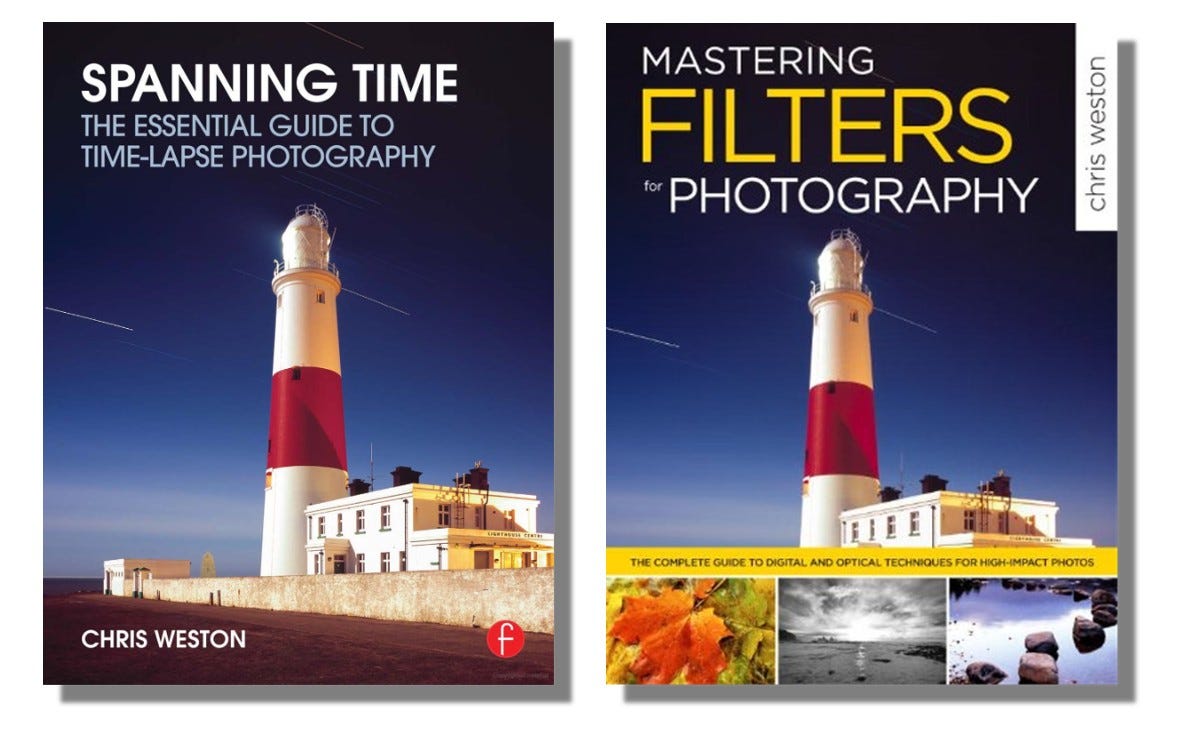

This citation in the above Wikipedia link is to Spanning Time: The Essential Guide to Time-lapse Photography, by Chris Weston, which is entirely out of print,3 despite being published only in 2015. It was published by CRC Press, who make technical manuals. This is not a film history book, nor is Weston any kind of historian.

The claim that Georges Méliès created the first time-lapse is mentioned only in passing in the introduction to the book, without citation—

Did Weston just make this up? Probably not. But he probably didn’t do any serious research, either. It’s not like he was writing a scholarly work; the whole thing seems kinda lazy. Heck, he used the same stock photo for the cover of an entirely different how-to manual:

So where did Weston get the idea to give Méliès credit? For that, we have to first look back at…

Folk Film History

The basic outline of early film mythology history goes something like this:

Prior to cinema proper, many inventors designed toys that relied on the persistence of vision, giving them fun names like zoetropes, zoopraxiscopes, and phenakistiscopes.

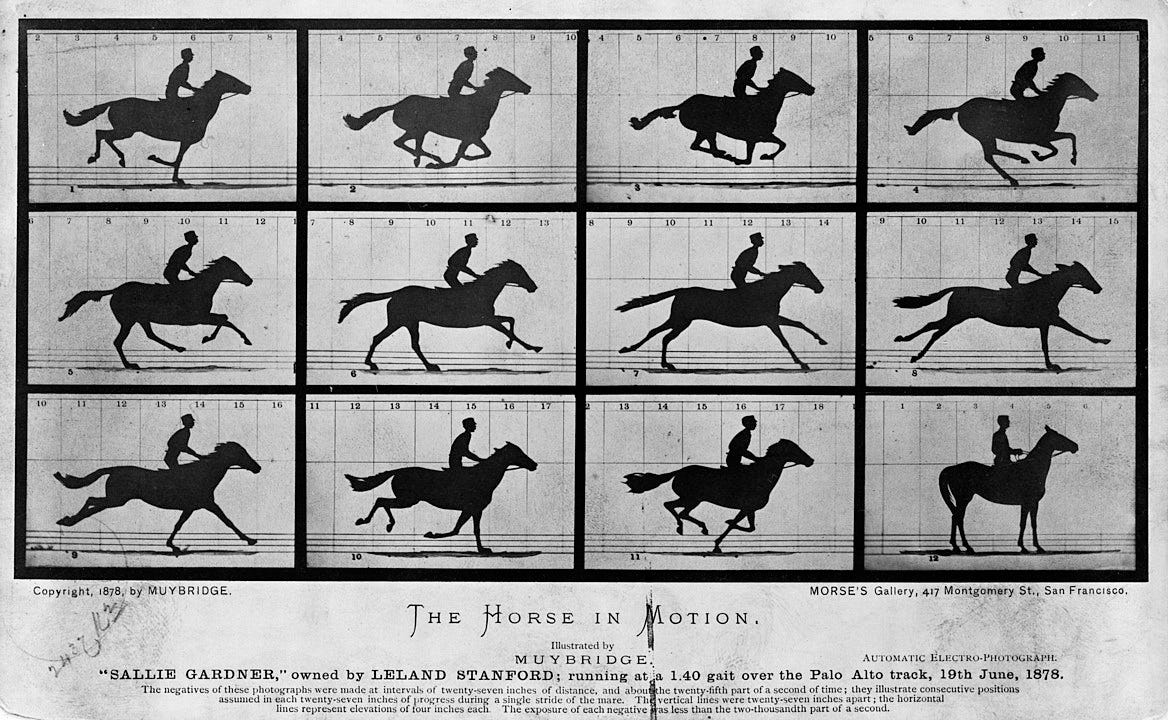

Then eccentric rich guy Leland Stanford hired crazy photographer Eadweard Muybridge to settle a bet over whether a horse lifted all four legs in the air at once or not. Muybridge rigged a dozen camera to strings on a horse track, and when the horse ran past, it triggered the camera shutters. The result was a dozen images of a horse in motion:

You’ve probably seen these spliced together in a little animation:

Soon, inventors were creating all sorts of new ways to rapidly record images and project them at such a speed as to give the illusion of movement. The first public screening of a motion picture was by the Lumière brothers, L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat, or the The Arrival of a Train:

The image so astounded the audience that they jumped from their seats and fled the room, for fear that the train would crash into them!

One audience member was magician Georges Méliès, who offered to buy their cinématographe (a combination camera, film developer, and projector). They refused, and so Méliès simply designed his own, and began making short films.

His skills as a magician made him uniquely suited to discover and developing camera tricks, like double exposure and jump cuts. And thus films evolved from mere factual documents to fantastic narratives.

The Legend Becomes Fact

That is, roughly, the story of early cinema, as it’s been taught in film school for more than half a century. It’s the “common knowledge” passed from one generation to the next.

Consider Martin Scorsese, one of the Movie Brats, the first generation of filmmakers to attend film school. He portrays a truncated version of this history in Hugo.4

The thing is, this history is not entirely accurate. Some elements are true, some aren’t. Scorsese, who’s forgotten more about cinema than I will ever know, surely was aware of this. But it makes for a good story, and in the movie it goes.

Take the bit about the Lumières’ train terrifying audiences (around 1:43 in the Hugo clip above). It almost certainly didn’t happen. Reporters did describe the train as seemingly “leaping off the screen,” but that was merely hyperbole to evoke a sense of wonder for newspaper readers who hadn’t seen the film.

And of course, most great movie myths are perpetuated by movies themselves. The Arrival of a Train urban legend was so popular, R.W. Paul made a film about a country bumpkin mistaking projections for real life, titled The Countryman and the Cinematograph:

The film was even ripped off remade by Edwin S. Porter the following year, as Uncle Josh at the Moving Picture Show:

Part of the appeal of this story is that it provides the viewer a sense of superiority. In the early 20th century, urban audiences could feel more sophisticated than their rural counterparts. Today, we moderns can look down on the ignorant people of a century ago.

Time’s Arrow

Okay, so the standard film history isn’t exactly history, but what about time lapse photography specifically?

Just like some stories of dubious origin get repeated, certain filmmakers receive undue credit, often because of their own relentless self-promotion. D. W. Griffith claimed (or was claimed to have claimed) to have invented close ups and intercutting. Orson Welles likewise gets over-credited for innovations supposedly introduced in Citizen Kane.

In the case of Méliès, he’s rightly considered the father of special effects. But because he’s the most famous name in silent-era effects, he’s often given credit for every early effect, including, in this case, time-lapse photography.

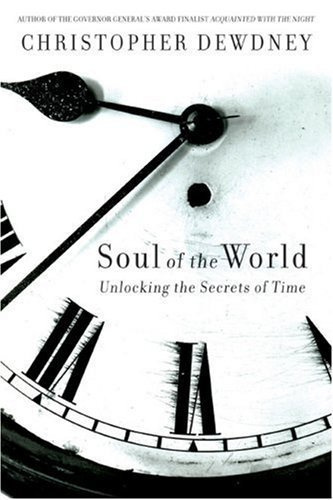

The film where he supposedly invented the time-lapse is Place de l'Opéra, 3d view (Paris), but that movie is lost. Wikipedia’s source for this is once again dubious—another out-of-print book, Soul of the World: Unlocking the Secrets of Time.

The author, Christopher Dewdney, is even less authoritative than Weston, who at least had an interest in photography. Dewdney is a poet, not a historian. One review of the book5 says he “often launches into quasi-philosophical reveries only to end up coming off sounding like a stoned college kid.”

Just like Spanning Time, we find an unsourced, unattributed claim:

I searched through several books on Méliès,6 looking for anything reinforcing this story, and came up with nothing. Zip. Nada. Not one real historian mentions time-lapse or Place de l'Opéra. But still, it’s weird that both authors cited the exact same film, isn’t it?

There’s actually a perfectly reasonable explanation for that.

Méliès’ Moment

Here’s a clip from the documentary The Méliès Mystery—

Yes, that is actually the voice of Georges Méliès.7 And it’s not the only time he’s related this story. Over the years, he frequently told interviewers about accidentally developing what he called the “stop trick” while filming in the streets of Paris.8

An obstruction of the apparatus that I used in the beginning (a rudimentary apparatus in which the film would often tear or get stuck and refuse to advance) produced an unexpected effect, one day when I was prosaically filming the Place de L'Opéra; I had to stop for a minute to free the film and to get the machine going again. During this time passersby, omnibuses, cars, had all changed places, of course. When I later projected the film, reattached at the point of the rupture, I suddenly saw the Madeleine-Bastille bus changed into a hearse, and men changed into women. The trick-by-substitution, called the stop trick, had been invented and two days later I performed the first metamorphosis of men into women and the first sudden disappearances that had, at the beginning, such a great success.

Notice that in both recitations of the anecdote,9 he was filming at the Place de l'Opéra. The location is just part of the story, as Méliès tells it.

So, he invents the substitution trick, basically builds an entire career out of it, and then subsequently tells everyone who will listen how and where he did it.

And yet, according to standard film mythology history Wikipedia, Méliès also discovered time-lapse photography in the same spot, but never used it again in any film throughout his career, and also never once mentioned the astounding coincidence of making both discoveries in the same location.

Does that seem at all likely to you?

Cinematic Citogenesis

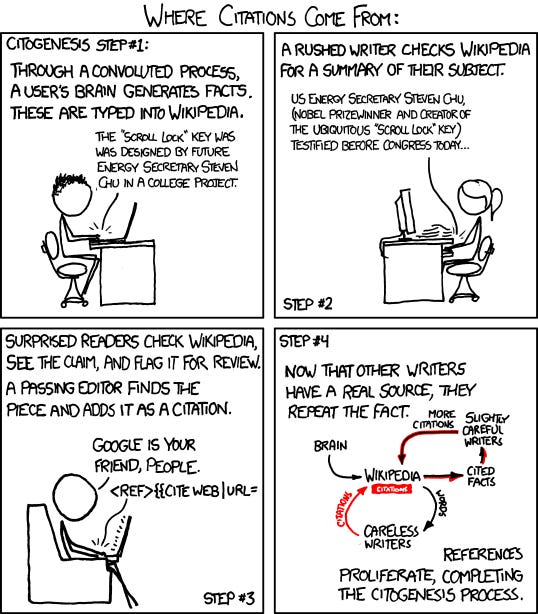

Here’s what I think happened. Someone read or heard Méliès’ story about the camera jam. Because of either the language barrier or just the evolution of film terminology, they misunderstood what he was describing.10 But hey, Méliès developed a lot of camera tricks, why not time-lapse photography, too? From there, it just became “common knowledge,” with no source. Until…

There is simply no evidence that Méliès created time-lapse photography. Just because someone printed it in a book one time, doesn’t mean it’s a fact. Try telling that to Wikipedia, though.

I don’t know if the Demolition of the Star Theatre is the first example of time-lapse in cinema history or not; it’s the oldest I could find. I don’t know if Place de l'Opéra, 3d view contained time-lapse photography; I couldn’t find any real record of that.

The fact is, I don’t know if anyone knows who invented time-lapse for what movie, or if we’ll ever know. It’s a question that’s been lost to time, now.

I told you this article would come to a disappointing conclusion.

She’s from New Zealand; I’m from Michigan. We met in Maine, as you would probably assume.

It’s coming, I promise!

You can get it print-on-demand from the publisher, but there aren’t any copies sitting on shelves at Barnes and Noble.

What a strange movie this is. I enjoy it, but it’s ostensibly a children’s film, and I cannot imagine an adolescent sitting through it.

And there aren’t many; this certainly isn’t the definitive history of early film.

For examples: Artificially Arranged Scenes: The Films of Georges Méliès, by John Frazer ; Fantastic Voyages of the Cinematic Imagination: Georges Méliès's Trip to the Moon, ed. by Matthew Solomon ; Marvellous Melies by Paul Hammond.

See what I mean about primary sources?

Les Vues Cinématographiques, 1907. If you read French, you can find the original here.

As an aside, it’s worth noting that this whole situation may not have happened. Edison had released The Execution of Mary Stuart the year prior, and it’s certainly possible, even likely, that Méliès had seen the film.

Technically, there was a time-lapse between those two frames before and after the jam, but who ever heard of a two-frame time-lapse?