Given that Independence Day weekend is traditionally one of the biggest weekends at the box office every year, I was surprised to learn that this year is the first time a Jurassic film was released on the holiday weekend. Most of them have released in June or late May.

I haven’t yet seen Jurassic World: Rebirth; it might be great, even if they missed the perfect opportunity to call it The Lost Park: Jurassic World. I’ll probably watch it by the time you read this; I’m a sucker for dinosaurs, and director Gareth Edwards’ chief talent is in creating a sense of scale.

Edward’s career has uneven. I loved Monsters and Godzilla, but as mentioned in a previous article, I didn’t care for his last film, The Creator (AKA Concept Art: The Movie). But far and away his most successful movie was Rogue One (clipped above), which has big, fat asterisk next to it, due to rumors of extensive re-shoots.

Four Dreaded Words

“Fix it in post” is a kind of anti-meme on film sets.

It’s a sardonic way of mocking directors who don’t plan their shoots properly (something I know a little too much about). Things go wrong on set, and rather than resolving issues then and there, they’ll kick the can down the road to post-production. This, in turn, leads to overworked visual effects technicians, cost overruns, and compromised visuals.

But even if the words “fix it in post” aren’t actually said on set, oftentimes mistakes aren’t discovered until the editing stage. If re-shoots aren’t possible, due to budget and scheduling constraints, filmmakers sometimes have to find creative ways of fixing them. That’s where the dreaded “back of the head” dialogue comes from.

So why do filmmakers try to fix things in post? The answer is simple

Sometimes It Works

Producers have been massaging scenes in the edit bay since the Golden Age of Hollywood. Irving Thalberg, for whom the special achievement Oscar was named, budgeted for testing and reshoots. And despite what the public is told, sometimes reshoots really do improve the movie.

Rumor has it that at least half of The Ballerina was heavily re-shot. Although the box office didn’t bear it out, I think the movie was pretty enjoyable.

The final scene in Seven was a last-minute addition, to give the audience some time to process what they’d just seen. Without it, the cut to credits was too abrupt. Likewise, Hitchcock appended a new ending to Foreign Correspondent as world events caught up to the film’s plot.

Sometimes, it’s the beginning of the movie that has to be fixed. My film Other Halves required some additional photography after a bad friends-and-family test screening. The original opening to the film centered on the villain, as is fairly common in horror movies. The problem was, that villain was also in every subsequent scene for the next 30 minutes, which led the test audience to thinking she was the main character.

Our editor came up with the brilliant idea of adding a fake commercial (featuring the actual protagonist explaining fictional Other Halves dating app) to the start of the film. We had originally shot it as a stand-alone teaser trailer, but it functioned just as well as an entry-point into the story. We then picked up a few shots of the lead actress to add to the credit sequence as a counterpoint to the villain, et voilà, now the real lead was in every scene, too.

Reshooting for the Stars

Not every movie is saved in the edit. In fact, there’s a persistent urban legend that the original Star Wars was radically altered in post-production, but that just isn’t true. See for yourself here—

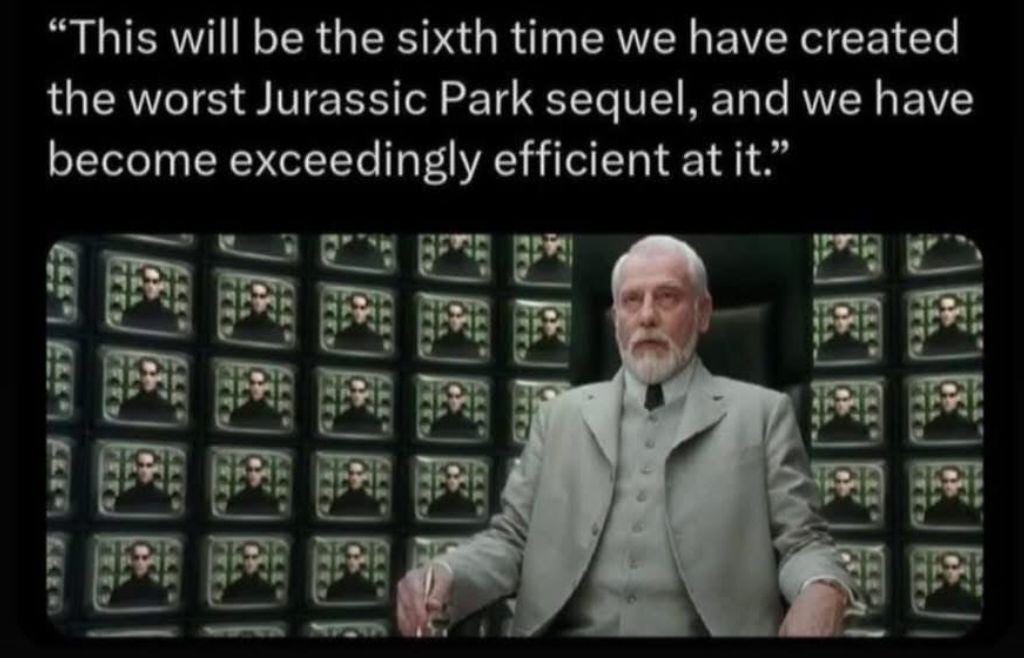

Speaking of Star Wars and circling back to Gareth Edwards, Rogue One underwent reshoots that were rumored to be quite extensive. But did they improve the movie? I know it’s the most beloved of the Disney Star Warses, but that doesn’t mean we got the best possible version of the film. We were promised Saving Private Ryan with Lasers, and what we wound up with is the claw game in space.

The beginning of the movie is kind of a mess, too. It seems to start about seven times before the plot actually kicks in. I’m half-convinced that fans’ fond memories are colored by the amazing trailers filled with shots that didn’t make it into the final cut.

Maybe Edwards’ version was a mess, and he needed Tony Gilroy to clean it up. After all, Gilroy produced Andor, which is great.

But on the other hand, the executives at Lucasfilm didn’t like the footage they were getting from Phil Lord and Christopher Miller on Solo, so they fired and replaced that pair with the OK-est director alive, Ron Howard. It became both the most expensive movie of all time (essentially shot in its entirety twice) and the least successful Star Wars film, even without adjusting for inflation.

So it’s entirely possible that Edwards’ director’s cut is even better than the Rogue One we all know and love. Or at least like. Or maybe tolerate.

Alas, we’ll never know. Releasing a director’s cut would leave the studio honchos open to criticism, should the public decide the new version is better than the theatrical cut. Personally, I’d like to see it. What about you?

Gaming Movies

For some reason, the third part of my trilogy of essays on video game adaptations didn’t get sent out to everyone. So in case you missed them, here are all the articles—