Aliens and Artificial Intelligence

On the depictions of AI in Hollywood

Ed: I meant to write this article after seeing Alien Romulus in theaters, but I’m a slow writer. So instead, I’m posting it now that it’s on streaming. That ought to please the algorithm, right?

Also: this article is unusually long, so if you’re reading this in your email, you may want to click on the headline and read directly on Substack.

Alien Romulus is basically a series’ compilation album, featuring all your favorite moments from the previous Alienses, mashed together into one film.

But that's okay. Going into the theater, all I wanted was a competently scary monster movie, and that's what I got. No complaints from me.

Beyond the creature,1 however, artificial intelligence has always been a part of the franchise. And while I don't demand anything more of the alien than that it burst out of someone's chest before trying to eat everyone else, the handling of AI is much more delicate—especially considering the post-Chat GPT/Midjourney world we live in.

Artistic Inclinations

Like most of the Alien series, Rolumus features an android. This time, it’s Andy.2

In previous entries in the franchise, robots were regarded as non-human, less-than-human, by the other characters. But in Romulus, Andy’s owner Rain treats him like an adopted brother. This follows a recent trend in Hollywood of anthropomorphizing AI. I don’t mean that in the sense of making robots look human. That’s been happening since the first cinematic robot—

But over the last decade or so, Hollywood seems to have been trying to convince audiences that robots are people, just like you and me. Everything from Chappie to The Creator to even this fall’s The Wild Robot wants us to empathize with the machines.

The pattern isn’t absolute, of course. Remember the “evil Alexa” movie AfrAId earlier this year? Neither do I. But there was M3GAN last year…3

On the flips side, the question “What measure is a robot?” has certainly been asked prior to the twenty-teens—

Still it feels, to me at least, like a genuine trend. It’s more than just “asking questions” about the (in)humanity of robots—all ambiguity has been thrown out the window now. There’s almost a concerted effort to assure the audience that artificial intelligence and human intelligence are indistinguishable.

It wasn’t always thus.

2001, The Matrix, The Terminator, and even the original Alien warned us that AI would try to kill humanity, or at least be indifferent to our passing. The fact that some of these robots appeared human only made them more terrifying. Today, if a movie robot looks human on the outside, we’re meant to accept everything about them is human-like.

The contrast between The Creator and Ex Machina, released nearly a decade apart, is illuminating in this regard.

The primary robot characters of each are designed to mimic sympathetic people—a young woman and a small child. They’re paired with protagonists who are extremely inclined to be drawn to the robots—a lonely young man and a widowed almost-father.

In the earlier film, Ava (the robot) manipulates Caleb (the young man), tricking him into doing her bidding, and [spoiler] leading him to his doom. In the later film, Taylor’s latent paternal instincts lead him to protect the small robot Alfie, and… that’s it. Becoming emotionally attached to an android built to look like the child he never had turns out to be a healthy lifestyle choice, according to the world of The Creator.

Alice In…

Allow me a moment to address what exactly is the difference between AI and people. This will be a slight digression, but trust me, I’ll come back around to the main point.

The difference is deeper than just synapses and circuits. The real distinction is that while AI can copy things, it doesn’t know things. To understand what I mean, consider the Chinese Room thought experiment—

tl;dw: imagine being locked in a room. There’s a slot in the door, through which someone passes you notes, all written in Chinese (or some language you don’t understand). Sitting on a table in the middle of the room is a book, with simple instructions—if a note says [this], write back [that]. It’s a large book, and seems to contain responses to every note that was passed to you. The responses you copy out are perfectly cogent, in Chinese. When they receive your replies, the person outside your room believes you read and write Chinese.

But can you really say you understand Chinese?

That’s what generative AI does—only the “book” is everything on the internet. And also, it can draw. But you get the idea, at least conceptually. The AI takes inputs, applies an algorithm, and spits out a result. A lot of times it’s relevant to your prompt; often, it’s not.

It’s enough to make one feel like Alice at the Mad Tea Party…

This is also the source of what are commonly called “hallucinations.” Or what Hicks, Humphries, and Slater identify as “bullshit.”

Recently, there has been considerable interest in large language models: machine learning systems which produce human-like text and dialogue. Applications of these systems have been plagued by persistent inaccuracies in their output; these are often called “AI hallucinations”. We argue that these falsehoods, and the overall activity of large language models, is better understood as bullshit in the sense explored by Frankfurt (On Bullshit, Princeton, 2005): the models are in an important way indifferent to the truth of their outputs. We distinguish two ways in which the models can be said to be bullshitters, and argue that they clearly meet at least one of these definitions. We further argue that describing AI misrepresentations as bullshit is both a more useful and more accurate way of predicting and discussing the behaviour of these systems.

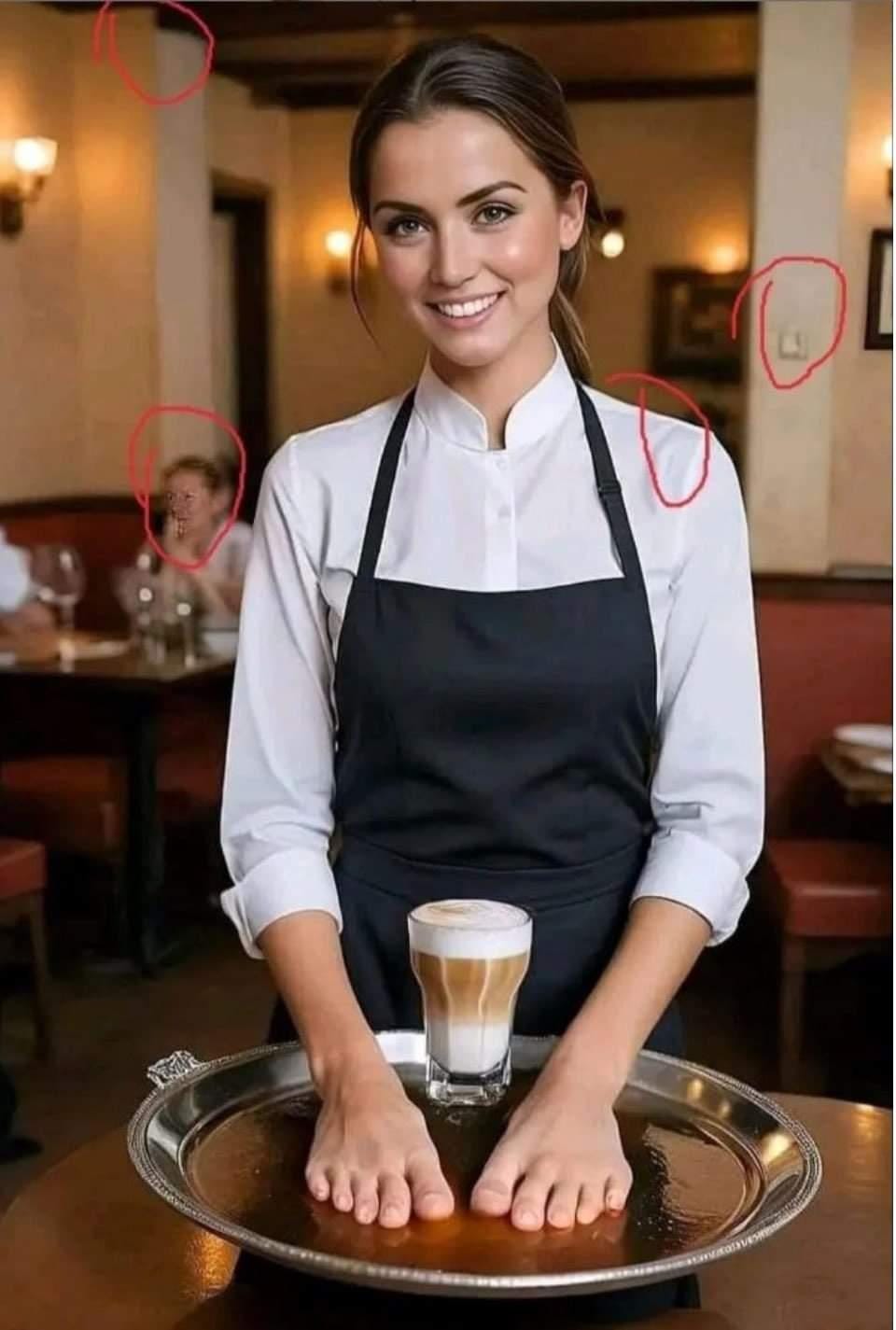

Likewise the bizarre artifacts that turn up in AI-generated images—

DALL-E doesn’t understand that feet don’t at the end of arms. It doesn’t know what’s wrong. It’s just putting together images it’s scanned in new ways.4 What these image generators don’t do is create meaning.

We do that.

Artifice, Incorporated

Pareidolia is the natural tendency in humans to see patterns, meanings, even where there are none. It’s why we see faces everywhere, for example.

Movies take advantage of this because—and I hope you’re sitting down while you read this—they’re not real.

Which is why a core task of the filmmaker is to create something that looks real. The actors pretend to be other people. Writers write dialogue that sounds natural. Production designers, visual effects technicians, costumers, and the rest of the crew all try to build a realistic setting (within genre expectations and the parameters of a given story world).

Cinema is a mimetic medium—movies resemble real life, superficially. And that’s good enough for us, usually. We don’t understand the physics of superheroes, but as long as it kinda, sorta, vaguely matches our preconceived notions of how a weight swings at the end of a rope, we’ll go with it.

It’s not just fantasy, however. Even the most naturalistic, kitchen-sink drama is ultimately a 2D image on a screen. It’s an assemblage of shots filmed hours or even days apart. And no matter how emotional the scene, it’s ultimately just actors hitting their marks and remembering their lines.

Filmmakers attempt to imply an inner life through external markers and performance. The audience are willing participants, willingly suspending their disbelief in all of that, and inferring inner life that flickering lights on a silver screen cannot have.

This is exactly how generative AI works on us. We see an inner meaning that doesn’t exist. And that fact—that the audience’s receptive process is the same whether the image is created by humans or algorithms—messes with the minds of creatives. In a sense, movies and TV shows pass the Turing Test: they trick the audience into believing they’re watching real people.

Is that so different from AI passing the same test?5

And so, when AI/robots/androids/artificial persons appear in movies, the filmmakers, from the writers to the directors to the actors, treat them as characters. Which brings me back around to Alien Romulus. Consider the way actor David Johnson talks about playing the android:

I wanted to make Andy, Andy. I actually think it’s a disservice when I say I wanted to make him my own, which I have said before, and it’s not true. On the page, he’s this brilliant character. He’s got almost two sides to him, and he’s going through a bit of a coming-of-age.

If you didn’t know any better, you’d think Andy was a person. Romulus missed a chance to do something truly different.

Almost Interesting

Like the previously mentioned robots, Andy is created in a sympathetic mold—this time because he is (or appears to be) mentally disabled. His owner treats him kindly, as she would a brother with special needs.

But he’s not her brother, he’s a robot. He’s not disabled, he’s malfunctioning. And any revulsion you might feel at hearing him described that comes, once again, from pareidolia. Andy looks like a human, because he’s played by a human. A disabled human deserves sympathy and care. It’s difficult to turn off that internal process when we see David Johnson on screen.

And I use the phrase “turn off” purposefully, because of what happens next.

SPOILER WARNING

Rain inserts a chip switch into Andy, which immediately upgrades him. His mental processing improves, as does his coordination. Even his accent changes. All of which clearly demonstrates Andy isn’t human. And yet, Johnson says:

Because of the nature of Andy’s switch, and him having the original chip put inside him — we wanted him to have that [accent], but at times, Ray looks at him and she’s like, Is he still there?

No, he’s not. Because “he” was never there, because he’s not a person. There’s nothing inside, because of the nature of AI. This is the missed opportunity of Alien: Romulus—to demonstrate for once that mimicking human behavior is not the same thing as being human.

In a lot of the Alien films, the android is a metaphor. Ash represents corporate greed, David unchecked scientific curiosity, etc.6 Andy appears to represent someone with special needs, until he’s not.

Romulus could’ve directly challenged our basic, but misplaced, empathy. It missed a rare opportunity to dramatize a lesson that we sorely need right now—artificial intelligence is not like human intelligence. In fact, it is entirely alien.

This post is much longer than I intended, and it kind of evolved into another “missed opportunity” post, like The Banality of Zone of Interest, but I suppose that can’t be helped. It’s just hard to ignore when a film almost does something interesting, then reverts to the standard.

Now that Coca-Cola has dived deep into the uncanny valley with their AI-generated ad, there’s more to say about how Hollywood uses AI in the production process, but I’ll save that for a later post. For now, what do you think about how Hollywood has portrayed AI over the years?

Not "xenomorph." People misunderstood the “xenomorph” dialogue in Aliens to mean the name of the creature. In fact, it was intended to be a generic military term for an unknown (life)form—which is what xeno and morph literally mean.

If the sequel isn’t called MEG4N, we riot.

Well, yes, but I’ll address that in a later post.

Feels a bit like we're being groomed for something, don't it?