Lionsgate finally granted Dan Harmon’s wish1 and announced Now You See Me 3: Now You Don’t.

I’m sure it’ll be terrible, just like the other two, but it does give me an excuse to talk about one of my favorite movies, Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige.

Processing Film

Nolan often gets criticized for focusing of the mechanics of a plot more than the characters. But certain genres really are about the process of accomplishing something, like heist films or con artist movies.

A heist film typically shows the elaborate planning that goes into stealing something of great value, including reconnaissance, enlisting the team, sometimes committing smaller crimes necessary to the execution of the big one. Then, we see the heist itself, when something inevitably goes wrong, followed by the aftermath. Depending on the style and filmmakers' interests, each of these parts may be emphasized or de-emphasized. The bank robbery is the central action set piece of Heat, but it's completely omitted in Reservoir Dogs, since it's not a particularly complicated robbery (and it saved the indie production a ton of money).

Con artist films are similar, except many of the planning details are kept obscure or unexplained until the big con at the climax of the film. Soderbergh’s Ocean's Eleven (which is both a con and a heist film) doesn't reveal the true purpose of the vault set until the end of the movie.

The sort of recap/revelation in the above clip is also common in movies about magicians, which can be seen as a genre hybrid of con game and showbiz drama. Like con films, magician movies promise to eventually show the audience how the trick was done. The difference is, magician flicks have another option—real magic.

Magical Duel

The phenomenon of “twin” or “dueling” movies is pretty well known. Two movies with similar concepts released suspiciously close together—incoming asteroids in Armageddon and Deep Impact; terrorists attacking the white house in Olympus has Fallen and White House Down; even a cartoon mouse interrupting a musical performance in Rhapsody Rabbit and The Cat Concerto.

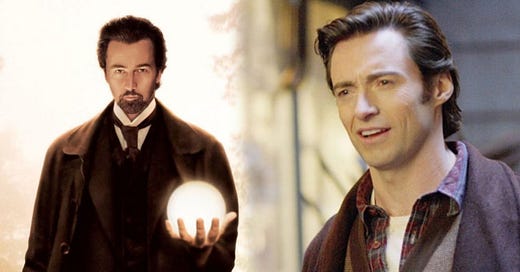

In 2006, Hollywood released two period pieces about magicians. One of them was set up as a prestige picture, with well-respected and award-nominated actors, an up-and-coming director, and serious artistic pretensions ambitions. The other was high concept: Batman Versus Wolverine… with Magic!2

Remember, Christopher Nolan wasn’t yet the brand name filmmaker he is today, one of the few who can open a picture based on name recognition alone.

Back then, Nolan had only one indie hit, Memento, and one studio blockbuster, Batman Begins, under his belt. He could’ve crashed and burned with too much money, two big stars, and a complex (some might say convoluted) story. And yet, The Prestige wound up being better than the “prestige” picture, The Illusionist.3

The Prestige is still Nolan’s best movie, which isn’t an insult to him, but a compliment to the film. And I don’t know, The Illusionist might be Neil Burger’s best, considering his oeuvre includes a Hunger Games knockoff and that moronic Bradley-Cooper-unlocks-the-other-90%-of-his-brain flick.

The key difference between them is the way they fulfill the promise of the genre.

A Magician Movie Always Reveals His Secrets

In The Illusionist, Eisenheim (Edward Norton) performs several tricks that baffle Inspector Uhl (Paul Giamatti). Particularly vexing is the “orange tree trick.”

Look, I can get past janky, early-2000s CGI as much as I can deal with jittery stop-motion in a Ray Harryhausen monster movie. Tiny imperfections don’t ruin a film.

Accepting the technical limitations of the time is just one form of suspension of disbelief. What I can’t accept is the explanation for this magic trick.

There is just no way that a box of gears could produce an edible orange. I’m sorry, this is just too stupid. Suspension of disbelief is one thing, but you can’t expel it entirely. It would’ve been better if Ed Norton just had been a literal wizard.

With The Prestige, Chris Nolan actually has it both ways. The film features two magicians, each with an impossible trick. And in the end, it’s revealed that one of these tricks is a “simple” illusion, while the other is, as Asimov Clarke4 puts it, sufficiently advanced technology, indistinguishable from magic.

The revelation of these two tricks perfectly encapsulates the two characters’ views of magic. Borden (Christian Bale) commits his entire life to the perfect trick; Angier (Hugh Jackman) is willing to pay for his prestige.

Borden’s trick strains credulity, but still seems within the bounds of physical reality. It’s a trick with an explanation. Angier’s trick is science fiction-bordering-on-fantasy, and thus doesn’t actually merit an explanation. Nolan has it both ways, because he has two magicians, each approaching magic and “magic” differently.

The Now You See Me films feature four5 magicians, and yet still manages to screw up this binary.

No, I Won’t See You

Now You See Me is a heist/magic/con-artist amalgam that combines all of the above elements into a blender, stirs them all up, then serves it to the audience who spits it all out because the resulting concoction is gross.

The end of NYSM tries to unveil multiple long-cons that have been running concurrently throughout the film, all while revealing the secrets of every trick in the film in such an absurd manner, it makes the clockwork orange from The Illusionist look reasonable. Essentially, they come across as wizards.

And you know what? It would be okay if they were wizards. It’s a movie, not everything needs an explanation. But if you are going to provide an explanation, it better make sense, especially in a con/heist/magic movie.

All of which is to say, I’m not going to see Now You 3 Me. How about you?

If you don’t know what I’m talking about, watch this compilation of his rants.

I recommend David Bordwell’s analysis of the former, Niceties: how classical filmmaking can be at once simple and precise:

Nolan’s audacious film is built out of marked parallels. Many films work varied repetitions like these into their shot-by-shot texture. Back in the 1930s, Eisenstein saw this possibility clearly, as I try to show in my book on his work. In the 1960s and 1970s, Raymond Bellour called our attention to such patterns in films by Hitchcock, Hawks, and Minnelli.

I wouldn’t go as far as Bellour does in seeing varied repetition as the motor force of classical filmmaking, but it surely plays an important role. What he takes as a manifestation of pure textual difference I’m inclined to psychologize: these differences help the audience understand, usually without awareness, the ongoing narrative dynamic and have the extra payoff of creating tacit narrative parallels. But from either perspective, object-centered or response-centered, studying such microforms is enlightening. It’s a way to understand films as wholes, dynamic constructions that shift their shapes across the time of their unfolding. Moreover, by examining things this closely, we can try to understand not only how this or that film works, but how this or that film relies on principles distinctive of a filmmaking tradition.

I’d add that such principles neatly fuse two pressures: toward narrative coherence and comprehension on the one hand, and toward production efficiency on the other. It’s cheaper and easier to repeat camera setups if you can. Artistic economy and financial economy can work together, nicely.

SPOILER ALERT: it’s actually more than four.

Most of "Now You See Me" is far-fetched but essentially plausible. Except at the end when they all jump off that rooftop and become CGI MONEY. I'm still waiting for an explanation.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com

Heh. One of my fave quotes. All good, then.